Years of protectionist trade policies and COVID-19 supply chain disruptions have set the stage for a more nationalistic approach to climate change and trade. This includes carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs), which are import fees or taxes applied by carbon-pricing countries to goods imported from non-carbon-pricing countries that stand to address carbon leakage and incentivize international climate action. But will CBAMs create a domino effect in climate policy and push more countries to act on climate, or will it lead to carbon trade wars?

What’s New

Carbon leakage is a threat to global emissions reduction. According to Carbon Market Watch, it is “the situation in which, as a result of stringent climate policies, companies move their production abroad to countries with less ambitious climate measures, which can lead to a rise in global greenhouse gas emissions.”

To protect markets and prevent carbon leakage, regions with strong climate policies and carbon pricing embedded into the cost of goods are beginning to introduce carbon border adjustment mechanisms (CBAMs), which can take the form of consumption taxes, import tariffs, or required purchasing of emissions permits upon import of goods from non-carbon-pricing regions. The latter is the mechanism the EU will adopt as part of the European Commission’s recent legislative draft proposal for climate action. The US has also announced plans to explore CBAMs.

CBAMs could incentivize climate action globally by establishing low-carbon economies as more trade competitive. They could push industries within jurisdictions facing CBAMs to lobby their governments for better access to renewable energy and more ambitious climate policies overall, including carbon pricing. This could challenge the view that transitioning to a low-carbon economy is economically uncompetitive.

However, there is a danger in entangling climate policy and trade.

Firstly, CBAMs risk stalling climate action by moving decarbonization from the domain of climate diplomacy to the arena of trade competition—and potentially even igniting conflict. CBAMs, if not implemented correctly, could become a cudgel in trade negotiations and incite retaliatory action from governments facing CBAMs on their products or even withdrawal from the Paris Agreement.

Current World Trade Organization (WTO) rules are designed to prevent a full-blown carbon trade war, and WTO compliance is important to ensure that CBAMs are not overly protectionist and remain in line with international trade regulations. However, ongoing diplomatic engagements are necessary to avoid retaliation.

Secondly, CBAMs could also incentivize companies to reshore or nearshore production away from countries without adequate climate policies, leading high-emitting countries to be disincentivized on climate action and creating potential "carbon clubs" of countries with similarly priced carbon.

Additionally, the overreliance of CBAMs on carbon pricing also means that some countries may be forced to pursue this policy route to participate in trade, creating an unfair disadvantage for those pursuing other legitimate means of decarbonization.

To mitigate these risks, it is essential that high-emitting countries are supported in their transition and have adequate access to capital, governance, and capacity-building to undertake climate action and respond to CBAMs. Without support to address these barriers, CBAMs could merely add to the fragility of economies, suppliers, and jobs located in these regions and further entrench a high-carbon economy.

Signals of Change

In March 2021, the Committee on Trade and Environment launched a Trade and Environmental Sustainability joint initiative group, which is expected to be a forum to address carbon border adjustments within the WTO.

In July 2021, the European Commission announced a draft proposal for the introduction of a WTO-compliant CBAM to be phased in by 2026 as part of the package of proposals intended to bring the European Green New Deal to life.

The US has expressed concern over the impending EU CBAM, urging the EU to delay the implementation while at the same time exploring its own possible CBAM.

The Mercosur Trade Agreement, in the works for 20 years, is now in contrast to the EU’s new trade strategy, which supports climate neutrality. The trade agreement is stalling over the EU’s stance on climate action, particularly in Brazil.

Fast Forward to 2025

If wealthy purchasing countries want to continue CBAMs, we demand that they first make good on their US$100 Billion Climate Finance Commitment...

The Fast

Forward

BSR Sustainable Futures Lab

Implications for Sustainable Business

As CBAMs begin to address carbon leakage, they will impact the pricing of goods along many companies’ supply chains. The first phase of the planned CBAM in the EU will apply to selected products at risk of carbon leakage: high-emitting products that also have a high level of trade with the EU and include iron and steel, cement, fertilizer, aluminum, and electricity generation. However, there is potential for carbon border adjustments to be extended to more products in the future—chemicals, paper, and glass were also under consideration.

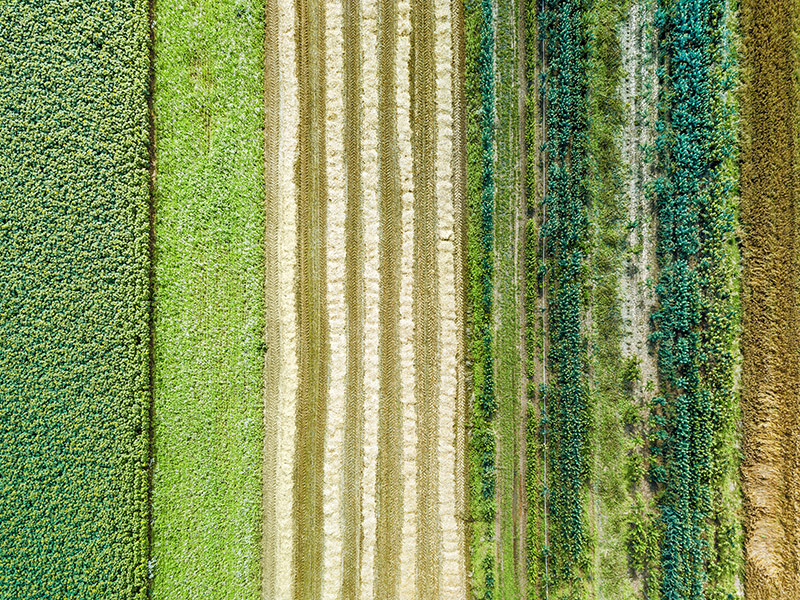

These industries, and those dependent on products in their supply chains, range from food, beverage, and agriculture to infrastructure and utilities, and they will need to consider the additional costs within their own supply chains. CBAMs should also be carefully designed so they do not unduly penalize workers in high-emitting industries, which would challenge climate justice and the just transition.

CBAMs will require a clear accounting of Scope 3 emissions as part of successful supply chain management. This will require increased supply chain transparency, traceability, Scope 3 data collection, and the ability to understand carbon flows. Companies can start to preemptively lower the carbon footprint of products and services to reduce their regulatory exposure to CBAMs in the future.

While it is not yet clear how all carbon border adjustments will be calculated in the future, companies will need to prepare for increased complexity of international trading, both in physical goods and in finance. Companies importing or exporting physical goods between countries with different climate polices will need to consider the implications that the coming CBAMs may have on their sourcing strategies and supply chain management. Companies will also need to enhance their competencies and capabilities to understand incoming regulations, such as mandatory climate risk disclosures, and revised trade policies.

National climate policy relies on multilateral cooperation. In theory, a carbon border adjustment could incentivize stronger climate policy and carbon pricing from exporting countries. But if, in practice, it backfires into a trade war or a withdrawal from the Paris Agreement, the consequences for the climate, and for all of us who rely on it, could be dire.

CBAMs will also make global investments and cross-border financial transactions significantly more complicated by restricting access to capital from investors in specific regions and increasing overall transaction costs. Already, differing expectations, regulatory schemes, and taxonomies are creating challenges for global investments. If carbon is eventually valued differently in different markets, or a product is considered high-carbon in one market but low in another, this could impact the financial valuation of international organizations or create opportunities for arbitrage.

However, there is also potential for CBAMs to push for better standardization of regulations and taxonomies internationally to ease compliance costs and promote trade.

![]()

Previous issue:

Micro-Factories

![]()

Next issue:

The Workforce Challenge of Long COVID