Climate change is driving migration and exacerbating other problems that cause people to leave their homes, such as food insecurity and conflict. Historically, governments and policymakers have been slow to address the issue. But there are growing signs that they are now paying more attention to the role that climate change plays in both internal and cross-border migration. As climate migration increases, businesses are likely to experience growing instability in their supply chains and operations, as well as challenges to their human rights responsibilities.

What’s New

As the climate changes, climate migration is on the rise. Climate-fueled disasters were the number one driver of internal displacement between 2009 and 2019. Around 20 million people per year had to leave their homes—80 percent of them in Asia. People were also three times more likely to be internally displaced by cyclones, floods, and wildfires than by conflict.

Other reports have found similar evidence of rapidly increasing climate migration. In the six months from September 2020 to February 2021, climate change-induced events like flooding and drought displaced 10.3 million people, according to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Many ended up in megacities, such as Dhaka and Jakarta, that already face climate impacts. Both are prone to flooding, for example, which is likely to become more severe as the climate changes.

Cyclones, floods and fires are the most visible drivers of climate migration, but they are far from the only ones. Along with such acute sudden-onset disasters, the chronic impact of climate change on temperatures, sea levels, and reliable rainfall will force huge numbers of people to leave their homes. One recent paper found that over the next 50 years, climate change could leave between 1 and 3 billion people outside the narrow set of climate zones where they’ve lived for more than 6000 years.

Importantly, not all of them will seek a new home in another nation: climate change is likely to drive more internal displacement than cross-border migration. The World Bank estimates that slow-onset climate change impacts, including water scarcity, crop productivity, and rising sea-levels, could cause 216 million people to move within their own countries by 2050.

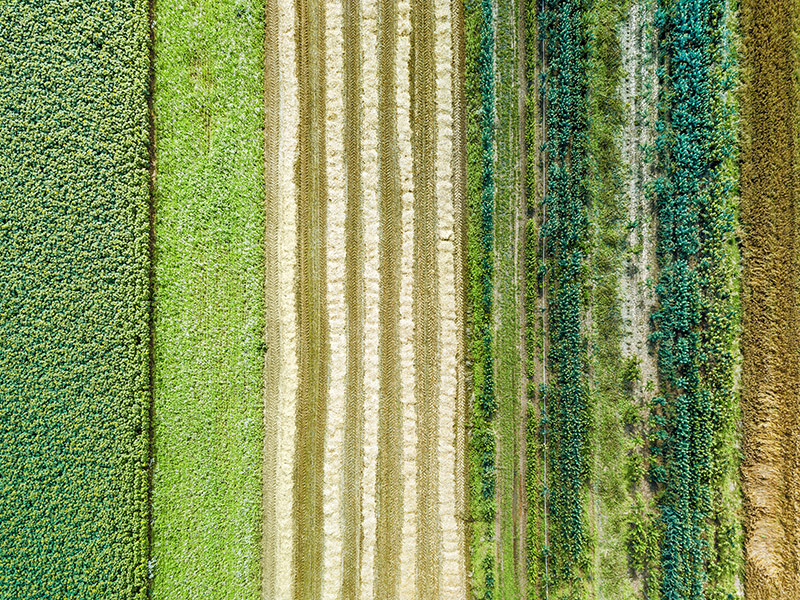

In terms of crop productivity, NASA predicts that climate change may affect the production of crops like maize as early as 2030. Maize yields are projected to decline by 24 percent due to increases in temperature, shifts in rainfall patterns, and elevated surface carbon dioxide concentrations from human-caused greenhouse gas emissions. These changes could make it harder to grow maize in the tropics and may drive internal migration. North and Central America, West Africa, Central Asia, Brazil, and China could see declining yields of this crop too.

Saltwater is also spreading further onto and beneath the land as sea-levels rise, storms grow more frequent, droughts increase, and people pump more water out of the ground. The salt harms plants and crops, threatens drinking water supplies, and could have a devastating effect on coastal farming. In California, for instance, up to one million acres of farmland may be lost in the next 20 years due to decreased water supply. In 2020, four Native American tribes living on the Gulf Coast of Louisiana also requested that the UN compel the US government to act on saltwater intrusion.

The tribes’ plight illustrates one of the most lamentable aspects of climate migration: that those forced to migrate today are typically from communities and nations that have contributed the least to greenhouse gas emissions. For example, seven of the ten countries facing the highest risk of internal displacement due to extreme weather are Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as Cuba and Tuvalu, where communities are 150 times more likely to suffer from it than those in Europe.

Although climate migration is most acute in SIDS, middle-class Americans are also on the move. Droughts and wildfires in states like California are driving people toward the cooler, calmer weather of the Great Lakes region. As a result, so-called “climate havens” like Duluth could face gentrification challenges, housing shortages, and increased pressure on local services.

Many other countries around the world are also experiencing climate migration—even if it’s not currently recognized as the cause of people’s movement from one area to another. It is likely to become a major policy issue for Asian, Sub-Saharan African, and Latin American governments over the next few decades.

The potentially huge scale of climate migration this century—and myriad knock-on effects on economies, cities, agriculture, and human rights—means it is receiving increasing attention from governments and international organizations. In January 2020, the UN Human Rights Committee ruled that it is unlawful to return people to their country of origin if that might place their lives under threat from the climate crisis—even if they don’t face immediate harm.

Groups such as the Climate and Migration Coalition are also calling for governments to mainstream climate change into their migration policies. Germany, however, has stated that it will not grant asylum to climate refugees. A spokesperson for the interior ministry said that although there was a link between climate change, migration, and flight, this link had so far been insufficiently investigated.

This is changing. In October 2021, the US Biden-Harris administration outlined the links between climate change and migration for the first time and recommended assessing how climate change may intersect with the criteria for refugee status. The report recognized that although most people moving due to climate change stay within their country of origin, cross-border migrations are rising, particularly where climate change interacts with conflict and violence.

In comments aimed at shaping the direction of the Biden-Harris report, Ama Francis of the International Refugee Assistance Project called on the White House to “take the necessary steps to fill the legal voids preventing climate-displaced people from finding a viable home.” Since publication, however, climate migration experts such as Amali Tower, founder and executive director at Climate Refugees, and Kayly Ober, senior advocate and program manager for the Climate Displacement Program at Refugees International, have expressed their disappointment with the lack of policy prescription in the report.

Bangladesh is also taking steps to address the needs of climate migrants. Researchers have been investigating how cities like Mongla and Khulna could be redesigned as refuges for climate migrants, thereby easing the pressure on Dhaka. Meanwhile, a new EU and International Organization for Migration project is targeting Somali communities affected by conflict and climate change. For 18 months, IOM will promote community-driven solutions aimed at mitigating natural hazards and environmental degradation—two known drivers of forced displacement and conflict—with a particular focus on investments in water access and management.

The extent to which climate change triggers or aggravates conflict remains hard to assess. It’s also difficult to disentangle climate change from the other socioeconomic factors behind migration, such as poverty and inequality. Nevertheless, in 2020, 95 percent of all conflict-related displacements occurred in countries vulnerable or highly vulnerable to climate change. Some experts believe that climate change was a contributor to the war in Syria, which began in 2011 after the worst drought in 900 years and a doubling of food prices (the conflict displaced roughly 6.6 million people). It can also make those forced to move by conflict more vulnerable, as in the case of the Rohingya refugees who fled violence in Myanmar, who now face flooding and landslides in refugee settlements in Southern Bangladesh.

Climate migrants may also face hostility from far-right groups when they seek refuge in another country. In the US and Spain, some of these groups have shifted away from climate denial and now cite protection of the climate and environment as reasons to stop immigration, even as climate change heightens the need for migration. This emerging strain of “eco-fascism” could exacerbate political polarization and harm social stability in many countries—yet another reason why governments, businesses, and civil society must properly prepare for increased climate migration today, while addressing the greenhouse gas emissions that are fundamentally driving it.

Signals of Change

In January 2021, a French appeals court overturned a Bangladeshi man’s expulsion order due to dangerous levels of pollution in his home country. In what’s believed to be a first-of-its-kind ruling in France, the court decided that the 40-year-old man could face respiratory failure as a result of an asthma attack if deported. The case could set a precedent for using environmental and climate change factors in future deportation cases.

In January 2022, Indonesia announced plans to name its new capital “Nusantara” when government offices are relocated from Jakarta to the province of East Kalimantan. The relocation of Indonesia’s capital, which is home to over 10 million people, was announced in 2019 but was delayed by the pandemic. The government hope it will reduce the pressure on Jakarta, which is one of the fastest sinking cities in the world due to excessive groundwater extraction.

In 2020, Puerto Rican native Olga González became the first Latina mayor of Kissimmee, Florida. Many ascribed the win to Puerto Ricans relocating to the suburb of Orlando following Hurricane Maria in 2017—a sign of how climate migration within the US mainland could change the political map in states like Louisiana, California, and Virginia.

The Fast

Forward

BSR Sustainable Futures Lab

Implications for Sustainable Business

Climate migration will affect many aspects of business, including operations, supply chains, the political environment, access to skilled workers, employee welfare, and responsibilities for upholding human rights, justice and equality. Businesses with operations and value chains in high-risk regions—notably Asia-Pacific, Latin America, and Africa—are likely to face the biggest impacts, along with those in the agriculture, transport, and energy sectors.

Even businesses with assets and operations in areas that are relatively resilient to climate change could see second-order risks from climate migration, as these areas are likely to attract people who have been forced to move. For example, if the population surges, a company’s operations may face water stress even if precipitation in that region has seen little change.

In last year’s data on internal displacement, we’ve seen three times as many people are displaced by climate-related events than conflict or violence…What we don’t really have an accurate picture on is the cross-border movement and what role climate plays in that…[But] we certainly know from indicators, from how mobility works and from where there are climate [change] hotspots, and from how climate intersects to widen inequalities and accelerate vulnerabilities…that climate is playing a very integral role in causing people to have to move in search of livelihoods and survival.

Changing demographics could also present new opportunities, especially in the property sector. Some cities could experience climate migration as a source of possible economic revival. Businesses operating in these host communities should consider how they can help the community support climate migrants—e.g., by providing employment schemes that will boost social stability.

Businesses need to plan now for a surge in climate migration. They should establish a climate adaptation and resilience strategy that takes account of the people in their value chain and potential migration issues and vectors. For example, organizations linked to coastal areas may need to consider whether they will lose human capital as rising sea levels force employees to relocate inland. Drought could have a similar impact on workforces and supply chains.

One recent study found that people tended to leave areas of Brazil that became drier for areas where they had social networks as a result of past migration. Where drought increased, employment in agriculture dropped significantly, jobs in the service sector saw a moderate decline, and manufacturing jobs increased sharply (perhaps due to falling labor prices).

In regions that received climate migrants, employment in agriculture and services rose but manufacturing saw no increase, possibly because climate migrants lacked the skillset for manufacturing jobs or because their social networks were disconnected from manufacturing firms. This pattern could potentially be replicated in other regions in the future.

Climate change and climate migration both exacerbate existing tensions and pressure for resources, and even galvanize eco-fascist sentiments. Any decrease in social stability also impacts supply chain stability, operations, access to talent and skills, and the strength of consumer markets. This speaks to the growing importance of building climate resilience on the community level.

Businesses must also consider the physical and mental safety of employees and supply chain workers who face displacement. People who move as a result of climate-related disasters or chronic climate impacts are at risk of human rights abuses, poor housing, lack of healthcare, low wages, and human trafficking, including sexual exploitation. One study by the IOM and the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI) found that fisheries, agriculture, forestry, and construction are both impacted by and involved in environmental destruction and forced labor in Asia.

“The environmental impacts of these sectors further aggravate vulnerabilities of communities, magnifying the role of environmental drivers on other migration drivers,” the IOM noted. “At the same time, migrant workers employed in these sectors are often known to suffer from exploitation.”

Businesses have a responsibility to ensure that the workers in their operations and supply chain are not subject to human rights abuses. As such, the human rights impacts of climate migration should be integrated into existing risk management processes. Where necessary, businesses should also perform targeted human rights impact assessments or carry out climate risk assessments that integrate a human rights lens (see recommendations 1 and 6 in BSR’s climate and human rights report).

For example, companies with extended supply chains should proactively investigate the welfare of migrant workers who have moved due to climate impacts (the risks they face include dangerous working conditions, stolen wages, assaults, and labor trafficking). A recent report by Anti-Slavery International and the International Institute for Environment and Development also concluded that “climate change acts as a stress multiplier to factors driving modern slavery.”

Women are particularly vulnerable during climate displacement and migration since structural inequalities deny them agency and expose them to violence—especially after disasters. The breakdown of infrastructure and chaotic movements of people make sexual exploitation easier and aid human trafficking for forced labor and the sex trade. In fact, of the 40.3 million people living in slavery worldwide, around 70 percent are female, with nearly three-quarters of these women trafficked for sexual exploitation. Since women are disproportionately impacted by climate displacement, climate migration could harm a company’s gender equity goals for the communities where it operates. Businesses should also be aware that the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the vulnerability of all climate migrants. For example, climate refugees now face closed borders, travel restrictions, and lack of access to handwashing facilities and medical care.

Businesses can act by ensuring people—and the issues that affect our communities—are integrated into climate strategies and net-zero commitments. This includes listening and understanding people most affected by climate change and co-creating solutions with underserved communities, pushing for policy change, protecting human rights, and building resilience to climate change across their value chains.

It’s important to note that slow-onset climate change impacts will also erode living conditions in some areas over an extended period. These areas are unlikely to be abandoned en masse. Instead, as noted in recent analysis published by Law 360, “climate migration may occur predominantly on the margins, as the carrying capacity or desirability of an area diminishes over time.”

By continuing to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, businesses can help to limit the severity of these impacts. Where possible, they should also explore other means of improving the resilience of these areas (e.g., reducing water usage) so that fewer people are forced to leave their homes because of climate change impacts.

![]()

Previous issue:

Carbon Capture’s Net-Zero Promise

![]()

Next issue:

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Take Flight