Across the world, fertility rates—the number of births per woman over her reproductive lifetime—are declining faster than predicted, with radical implications. A 2020 study forecasts the global population in 2100 will be 2 billion less than previously projected. The implications of a rapidly aging and decelerating population are wide-ranging, affecting workforces, family structures, infrastructure, and social care provision, as well as international economic migration and geopolitics.

What’s New

The human population tripled in size in just 70 years, from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 7.7 billion in 2020. This focused sustainability discussions on the question of how to improve or maintain living standards for as many as 9 billion people while working towards global goals for reducing resource use and greenhouse gas emissions.

Now, birth rates across the world are declining sharply while people are living longer. A 2020 study published in The Lancet projects that the global population will peak in 2064 and decline to 8.8 billion by 2100: that’s over 2 billion fewer people at the end of the century than the UN had forecast in 2019. And since 2018, for the first time in history, most people can expect to live into their sixties and beyond. This both reflects improved living standards and poses new challenges.

Half of all countries already have fertility rates below population replacement levels. Even low- and middle-income countries associated with rapid population growth, such as India and Mexico, are now experiencing slowing rates. High-income countries in Asia, including Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, are experiencing “ultra-low fertility.” This trend is expected to snowball, and the global population is projected to enter its first-ever sustained decline by the middle of the century.

Socioeconomic factors play a critical and complex role. In the Global South, women’s empowerment, through increased access to education, labor markets, health services, and contraception, has contributed to declining fertility rates. In Africa, which has the world’s highest fertility rates, the declining number of children per woman reflects rising education levels alongside urbanization. Nigeria is poised to become the third most populous country in the world by 2050, and increasing education by one year was found to reduce fertility by 0.26 births. A study in Ethiopia found that women with eight years of schooling would have a fertility rate 53 percentage points lower than those with no schooling at all. Job security is also a factor: in Ghana, which has a high but falling fertility rate, women with more secure jobs are having fewer children.

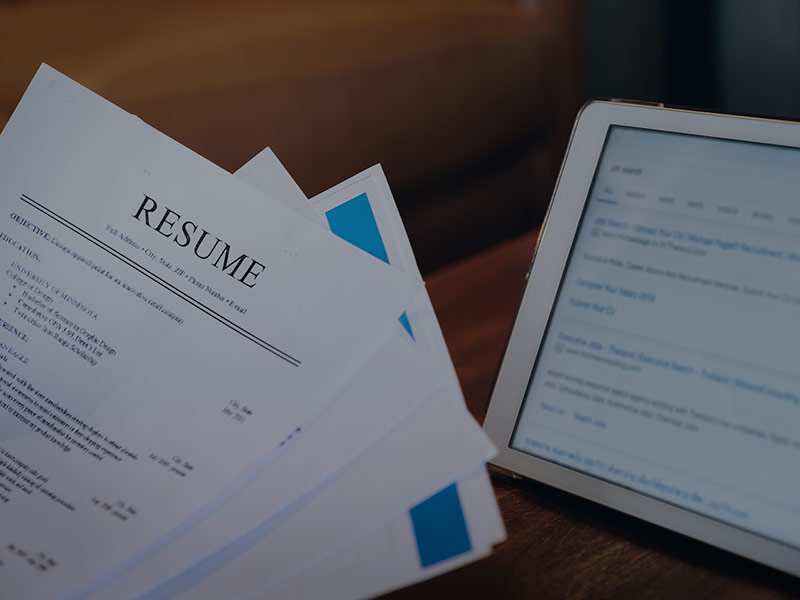

While falling fertility tells a tale of empowerment and development in the Global South, in high-income countries, the choice to defer having children can also signal barriers to equal opportunities in the workplace for pregnant women and mothers, alongside high work demands and living costs. A US study found that job applicants who didn’t reference children were twice as likely to get called in for an interview. In Denmark, the arrival of children creates a gender gap in earnings of around 20 percent, driven in roughly equal proportions by labor force participation, hours of work, and wage rates. In South Korea, where the gender pay gap is 34.6 percent (well above the OECD average of 13.1 percent), studies show a correlation between women’s greater workforce participation and the world’s lowest fertility rate.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated declining fertility rates, largely due to the burden of care for families and its disproportionate impact on women. Not only has homeschooling impacted the capacity of women to maintain employment, but it may have affected sexual activity. The Brookings Institute estimates that the pandemic will result in at least 300,000 fewer births in the U.S.

Advances in healthcare have played a role in doubling the average human life span between 1920 and 2020 and will continue to have an impact. This year, Japanese researchers used tissue engineering to reverse the aging of knee cartilage, while Israeli scientists have reversed skin aging with oxygen therapy.

Signals of Change

China is trying to mitigate a rapidly aging population 40 years after introducing its one-child policy. In 2016, it revised the policy to allow for two children, and in May of this year, again revised the policy to three. The latest census shows China is experiencing its slowest growth rate since the 1960s.

Through a “Talent Boost” program, Finland aims to attract skilled immigrants to boost an aging population and workforce. The government warned that it needs to double immigration levels in order to maintain public services and pension schemes.

Matthew Yglesias, an economic and political journalist, released a new book, One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger, which argues that the only way the US can remain an economic superpower is to triple the country’s population to a billion.

Research points to the connection between unhealthy environments and lifestyles and declining fertility rates. Chemicals such as hormone-disrupting phthalates are increasingly found in plastics and household goods and may be harmful to reproductive health.

Fast Forward to 2025

We had to make the Circular Employment Program mandatory a few years back since some people refused to vacate their roles...

The Fast

Forward

BSR Sustainable Futures Lab

Implications for Sustainable Business

These faster-than-expected demographic shifts pose extraordinary opportunities and challenges for society and sustainable businesses. On the one hand, shifting away from rapid and unsustainable population growth reduces pressure on resources, from food and healthcare to land, materials, and commodities. On the other hand, it will mean higher dependency ratios, strain the global workforce and social benefits, and can lead to a loss of productivity and innovation. The choices businesses make today will play out over generations and across society.

Countries will need to find the resources to support much longer lifespans. In the OECD alone, the dependency ratio of people over 65 as a proportion of those aged 20-64 (currently considered working age) will rise from 22 percent to 46 percent by 2050. This means that there may not be enough people to care for an increasing number of dependents, including fewer workers paying into social security schemes.

Labor markets can offset the cost by absorbing or retaining older workers. Hong Kong introduced measures to promote the employment of older workers in 2018, including extending the retirement age of civil servants from 55-60 to 60-65, wage subsidies for employees over 60, and training and job fairs for mature workers. Startups such as Wise at Work help companies find older candidates, bringing valuable experience and perspectives, and run training activities to address the challenges of multigenerational working.

To accommodate workforce shortages and the ‘100-year life,' highly customized workstyles and re-learning are critical. Additionally, partnerships between companies are increasingly important for resource allocation, which can help to minimize volatility risks.

Companies are benefiting from policies to attract and retain a wider range of applicants. Best practices in diversity, equity, and inclusion, such as flexible hours and locations, paid personal leave, and increased access and support for people with chronic conditions and disabilities, have been shown to increase innovation and productivity across the board.

Businesses can promote reproductive choice by reducing the gender pay gap and advocating for LGBTQ+ rights to parenthood as well as at work. Recommendations include addressing bias in hiring, running pay audits, giving women more visibility, holding HR departments accountable, making sure leadership positions are equitably filled, and empowering mothers to return to work and advance their careers.

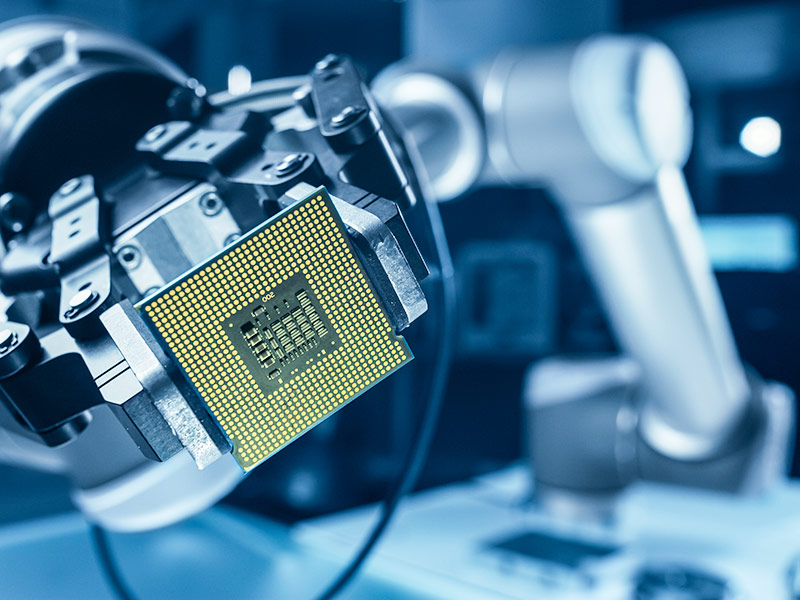

Increasingly, gaps may also be filled through automation, with risks to those made redundant. Population aging can explain almost 40 percent of the country-to-country variation in the adoption of industrial robots, researchers have found. Policies such as the taxation of automation and artificial intelligence, alongside workforce subsidies, may help to achieve a better balance between the social gains of increased efficiency and productivity and the costs of unemployment or worker displacement. Businesses should prepare.

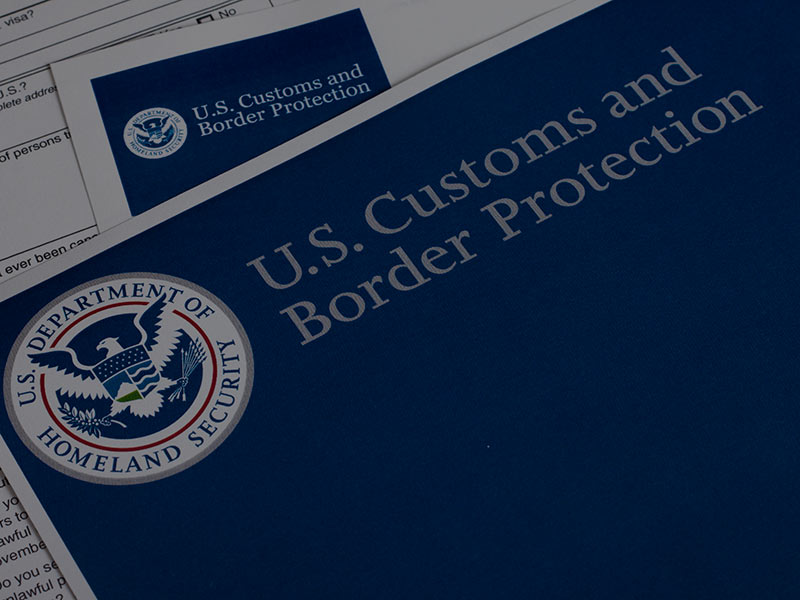

Another strategy to replace lost workers is importing labor, with risks for low-wage migrants where inequalities can drive social unrest. Countries experiencing high levels of emigration face risks, from drained communities and stressed social structures to falling levels of productivity and innovation, as fewer people focus on research and development. Competitive employment markets are therefore critical to future economies, while an increase in protectionist policies could impede the ability of companies and sectors to recruit international workers and laborers.

New models are required for social protection, especially for healthcare and retirement. Private life insurance, long-term loans, and healthcare coverage will be important to bolster costly pension schemes that depend on a large workforce paying into the system to fund retirees, but equitable access is key. Employees will increasingly look to companies to help them meet present-day needs and ensure a secure future, with precedents.

Ideas of a country's economic well-being are currently assessed largely based on the evolution of GDP, which is in turn driven to a significant extent by population growth, and will need to be redefined. Similarly, demographic shifts are poised to alter how society is funded and how those funds are distributed. The social contract, or relationship between individuals and institutions, may become a centerpiece of society, with corporations taking on larger roles in providing social services and protections. Without the same checks and balances that governments operate under, shifts to greater corporate involvement in every aspect of life raises questions about power, social responsibility, and accountability.

The OECD warns that demographic shifts, combined with climate change, rising inequality, and new technologies, create fragility risks for both low- and middle-income societies. The business community needs to protect and invest in its future workforce.

![]()

Previous issue:

A Scramble for Battery Minerals

![]()

Next issue:

Nature’s Rights Go to Court