Searching for:

Search results: 1061 of 1137

Blog | Monday January 9, 2017

Sustainable Business Leadership in 2017: Game On

Looking ahead to a new year with new conditions, here is our suggested playbook for how business can lead in this new environment.

Blog | Monday January 9, 2017

Sustainable Business Leadership in 2017: Game On

Preview

At the start of last year, we were still riding the highs of 2015, which saw important progress on sustainable business. The year just past, 2016, for multiple reasons, was less positive. How will 2017 break the tie?

Let’s start by looking back to where we were a year ago. Here’s the good news: The twin successes of 2015—the Sustainable Development Goals and Paris Agreement—set a powerful long-term agenda for decades of progress. But as the year unfolded, this sense of progress dwindled as we witnessed the Brexit vote, refugee crisis, and terrorist attacks in Europe; the Trump election in the United States; and declining support for civil society around the globe.

And yet, serious though they were, the events of this past year need not represent the new normal. Looking ahead to a new year with new conditions, here is our suggested playbook for how business can lead in this new environment.

Stay true to the values underlying sustainable business: As I wrote in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. election in November, it is essential during times of change to stay true to enduring values and principles. Sustainable business is premised on respect for people and communities, basic fairness in the economy, and preservation of natural resources and the environment to ensure prosperity for future generations. These values continue to guide us at BSR and underpin all our work with member companies and other partners. Indeed, the 2016 U.K. and U.S. election results in many ways reinforce, rather than contradict, the importance of economic fairness, even though the results may not deliver the outcomes many of us want. Our values will continue to serve as a north star throughout 2017.

Increase the commitment to economic fairness: Just as we remain steadfast in our values, we cannot be blind to the anger and resentment expressed by many during the past year. We need to acknowledge the views of many that our economies do not enable all to participate fully. The sustainable business agenda therefore needs to prioritize economic fairness more fully. This means attention to multiple issues, including inclusive economic growth, preserving quality jobs in the age of automation, gender equity, and executive pay. In 2017, BSR will be expanding our efforts in inclusive economy issues, along with new ways of looking at the connection between environmental sustainability and jobs.

Accelerate irreversible changes to the energy system: While the apparent hostility to climate action from the new American administration is highly problematic (and unwise), progress on climate will continue for a number of reasons. First, the cost of renewables is plummeting, and new technologies are improving on a similar pace, creating an unassailable economic argument for continuing the transition to low-carbon models. Second, new business models (such as distributed energy systems) and new products (such as longer range electric vehicles) are coming into the mainstream. Third, many of the highest growth markets—think China—remain steadfast in their commitment to a shift to cleaner energy. Finally, states and regions have no intention of making a U-turn on their shift to low-carbon models, regardless of Washington’s policies or Europe’s dysfunction. For these reasons and more, the vision of the Paris Agreement remains not only intact, but vibrantly alive. BSR will continue to aid companies on their own climate strategies, as well as to work through partnerships like the Renewable Energy Buyers Alliance and We Mean Business to ensure that progress continues.

Promote innovation: The nostalgia for past grandeur that is driving politics in many parts of the world misses the point. New business models, new technologies, and new ways to access products, services, and experiences are changing fast. The pace of change may be distressing for many, but the essential nature of change is on balance positive, and is essential to truly inclusive growth that the past never achieved. As BSR looks to redefine sustainable business in the year ahead, we will explore how to build on new models (such as the inclusive sharing economy), new products and services (such as access to renewable energy), and new partnerships (such as the Global Impact Sourcing Coalition) to advance new solutions to ongoing sustainability challenges.

Raise the voice of business: Finally, in our new political environment, the voice of business needs to remain strong and clear about the importance of sustainability. Business is global, and despite market pressures, smart companies make decisions intended to last well beyond the next election. As we have noted since the success of the Paris climate negotiations in late 2015, the private sector can do itself and wider society a favor by reminding policymakers of the importance of the sustainability agenda. BSR will work with our member companies in the year ahead on climate advocacy, the protection of human rights, and the development of reporting and market frameworks that advance long-term value creation.

All in all, despite the multiple shocks of 2016, we see many reasons for optimism. And yet, optimism unmatched by commitment is an empty wish. With that in mind, let us redouble commitment to building a just and sustainable world, based on core principles, and with strategies that are adapted for changing realities and that address the very human aspirations underlying the turbulence of 2016. In doing so, we will see ongoing progress and reason for renewed optimism at the end of this pivotal year.

Blog | Friday January 6, 2017

Five Ways the Financial Services Industry Can Approach the Sustainable Development Goals

There are many opportunities for financial services companies to fund the SDGs, and they should look at how to integrate the goals into these five areas.

Blog | Friday January 6, 2017

Five Ways the Financial Services Industry Can Approach the Sustainable Development Goals

Preview

It is estimated that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in late 2015, will cost between US$90 trillion and US$120 trillion by 2030. In this light, there is no doubt that the financial services industry has a role to play in funding the objectives. There are many opportunities for investors and banks to fund the SDGs, and in the past year, banks and other companies have explored what these global goals mean to them.

The 17 goals provide a useful reference for banks and other financial services companies to understand and measure how they contribute to sustainable development. Financial services companies, including institutional investors, banks, and credit card companies, should look at how to integrate the SDGs into communications, stakeholder engagement, goal setting, impact measurement, and partnerships.

All 17 of the SDGs require funding. But with 169 targets, the goals are not easy to navigate. To address this, financial services companies can choose to focus commitments on a small number of goals on which they have the most impact. These are the goals closest to their core business—rather than niche business, internal efforts, or philanthropic efforts—and that represent an opportunity, such as funding affordable and clean energy (Goal 7), rather than managing a risk, such as ensuring investments do not harm the oceans (Goal 14). Following a review of what financial services companies are currently focusing on, we found that the most relevant SDGs for the financial services sector are Goal 1 (no poverty), Goal 5 (gender equality), Goal 8 (decent work and economic growth), and Goal 13 (climate action).

In the past year, some financial services companies have used the SDGs to communicate, engage, set new goals, measure impact, and build new partnerships. Financial services companies should think about how to integrate the goals into these five areas:

- Communications: The SDGs provide a framework to communicate on how financial services companies contribute to economic development and the creation of jobs. For instance, MasterCard communicates on how its core business supports and advances five specific SDGs. And Credit Suisse published a paper on how it contributes across the SDGs with case studies on four specific goals.

- Engagement: Banks can use the global goals as a platform to engage stakeholders—including staff, clients, regulators, and NGOs. For example, Standard Chartered launched a campaign to raise awareness among employees and clients about the SDGs. Credit Suisse held workshops in Zurich and Hong Kong with government agencies, development banks, and civil society to identify priorities for action.

- Goal setting: Some investors and banks are using the SDGs to set new goals. The Dutch Pension funds PGGM and ABP have set ambitious targets to invest €58 billion in investments that support the SDGs by 2020. BNP Paribas tracks the percentage of corporate loans granted to businesses that made a specific contribution to the SDGs and has a goal to maintain this key performance indicator at 15 percent for the next three years.

- Impact measurement: Additionally, the goals provide a proxy for measuring impact. For instance, when MasterCard sets out to reach 500 million people previously excluded from financial services by 2020, it helps to know that Goal 1 specifies that it hopes to ensure 2 billion unbanked people receive a bank account. Investors should be wary of the risk of “SDG-washing,” if they are too quick to label funds as supporting the goals, without measuring impacts. Investors should have clear common guidelines on what constitutes an SDG investment and should measure the impacts of their investments.

- Partnership building: Partnerships are key to the success of the SDGs. The goals can help galvanize a broader community and bring new partners to the table such as governments, multilateral institutions, and clients. For example, a MasterCard partnership with UN Women aims to drive financial inclusion of women. With its pilot in Nigeria, the partnership will provide half a million Nigerian women with identification cards that include electronic payment functionality. Barclays has built longstanding innovative partnerships with clients such as GSK and NGOs such as Care International to support access to healthcare and financial services.

The SDGs represent a strong framework for companies to use in defining sustainable development commitments. Banks and other companies should seize the opportunity to align their business strategies to the goals. This also includes moving beyond the important first step of communicating on what a company is doing to setting new commitments on investing in sustainable development solutions and measuring the impact of these investments.

Blog | Thursday January 5, 2017

A Conversation with Joel Makower and Mark ‘Puck’ Mykleby at the BSR Conference 2016

Joel Makower and Mark Mykleby presented the bold ideas of their book “The New Grand Strategy” in a plenary session moderated by Aron Cramer at the BSR Conference 2016.

Blog | Thursday January 5, 2017

A Conversation with Joel Makower and Mark ‘Puck’ Mykleby at the BSR Conference 2016

Preview

In a plenary session moderated by BSR CEO Aron Cramer at the BSR Conference 2016, Mark "Puck" Mykleby and Joel Makower highlighted bold ideas presented in their book, The New Grand Strategy.

"Ask people what kind of world they want for their kids and they will speak in the language of sustainability," Mykleby said. Mykleby is codirector of the Strategic Innovation Lab at Case Western Reserve University and a retired colonel of the U.S. Marine Corps. Makower is chairman and executive editor of GreenBiz Group Inc.

Watch the full video below:

The BSR Conference 2016, which took place November 1-3 in New York, gathered sustainability leaders from business, government, and civil society to explore the theme of “Be Bold.” Check out the conversation on Twitter at #BSR16 and see all video highlights on BSR’s YouTube channel.

Blog | Monday January 2, 2017

Thinking the Unthinkable with Nik Gowing

From the BSR Conference video archives: a speech by Nik Gowing, co-author of “Thinking the Unthinkable” and former BBC news anchor, followed by a conversation with BSR Board Chair Alessandro Carlucci and BSR Non-Executive Board Director Karina Litvack.

Blog | Monday January 2, 2017

Thinking the Unthinkable with Nik Gowing

Preview

In a plenary address at the BSR Conference 2016, Co-Author of Thinking the Unthinkable, Visiting Professor at King’s College London and Nanyang Technological University, and former BBC news anchor Nik Gowing explored how being bold can help build a better world.

“It’s not really the company, it’s actually the human beings inside,” Gowing said.

Following his address, Gowing joined a conversation with former Natura CEO and BSR Board Chair Alessandro Carlucci and BSR Non-Executive Board Director Karina Litvak and answered live questions from BSR Conference participants and Twitter.

Watch the full video below:

The BSR Conference 2016, which took place November 1-3 in New York, gathered sustainability leaders from business, government, and civil society to explore the theme of “Be Bold.” Check out the conversation on Twitter at #BSR16 and see all video highlights on BSR’s YouTube channel.

Case Studies | Tuesday November 22, 2016

Instituto Avon and Fundo ELAS: Speak Out Without Fear Fund

Instituto Avon and Fundo ELAS: Speak Out Without Fear Fund

Case Studies | Tuesday November 22, 2016

Instituto Avon and Fundo ELAS: Speak Out Without Fear Fund

Preview

This case study was developed by Win-Win Strategies in support of the Investing in Women initiative, a collaboration platform providing companies with opportunities to share, learn, and design effective approaches to women’s empowerment.

Background

The partnership between the Instituto Avon in Brazil (Avon) and Fundo ELAS (ELAS) grew out of a common interest in addressing violence against women. The issue of domestic violence has long been at the center of Avon’s social investment strategy, as it is critical to its largely female employees and customers. ELAS, with its focus on investment in women’s leadership and rights, has supported numerous women’s organizations in Brazil that have worked for many years to address the issue of gender-based violence and create social change.

In 2009, Amalia Fischer, then executive director of ELAS, was invited to speak at Avon about ELAS’ work. Following that meeting, Avon and ELAS began working together to develop a partnership aligned with both organizations’ goals. This partnership led to the development of a fund called Fundo Fale Sem Medo, or the Speak Out Without Fear Fund, which is now in its third year.

Together, Avon and ELAS designed the launch of the fund and completed all supporting communications and strategy. As part of this partnership, ELAS runs a competitive process each year to award grants to projects designed by local women’s organizations that utilize innovative approaches to address the issue of domestic violence.

The program is currently funding 31 organizations, with projects ranging from a rock music festival that highlighted women’s rights and domestic violence prevention, to a program that uses sports as a vehicle to teach girls about their rights and help prevent violence. The program also provides workshops on how to reduce gender-based violence and brings the grantee organizations together for capacity-development and to foster collaborations among them.

The Strategy

The decision to support ELAS was based on Avon’s view that to address an issue like domestic violence, it was important to work with strategic players with credibility and a proven track record. This type of relationship is core to Avon’s approach of working in partnership with other organizations and with NGOs with direct links to the issues of interest to Avon.

Avon and ELAS share the perspective that the most appropriate and effective strategies to end violence against women are those that involve local women’s organizations. In working with ELAS, Avon has a partner with knowledge of these organizations, experience in the community, and the ability to support locally relevant solutions. As Lirio Cipriani, the executive director of the Avon Institute noted: “In order to face this pressing, challenging, and widespread issue, we must cooperate with strategic players in a coordinated manner. Supporting women’s organizations is essential; we recognize that their work has led to important institutional transformations and strengthened the support network that can serve women in violent situations.”

Over three years of funding to ELAS, Avon has supported 77 projects to fight domestic violence in Brazil, and ELAS has received a total of 7 million Brazilian reals (equivalent of more than US$2 million) from Avon to support the selected grantee projects. During the project period, in addition to written progress reports, ELAS and Avon have held regular face-to-face and virtual meetings, working together in a transparent manner to monitor the projects, develop and revise assessment tools, and ensure effective collaboration.

Two key factors were highlighted as contributing to the success of the partnership:

- ELAS and Avon have shared values and a shared interest in social investment to support social transformation and women’s empowerment. In particular, they both believe that empowering and financially supporting local women’s organizations is an important strategy to stop violence against women.

- ELAS and Avon each appreciated each other’s mission and expertise. ELAS reported that Avon understood the experience and knowledge that ELAS brought to the table. ELAS also reported that it knew of the work that Avon was doing to empower women and valued its commitment to end violence against women, reflected in Avon’s other partnerships with the public sector and civil society.

Impact

Both parties are inspired by the work they have been doing together to address the issue of domestic violence in Brazil and have seen positive impacts on women in the organizations reached. Nonetheless, Avon identified measuring impact as a challenging area, as specific measurement indicators were not part of the first and second years of the Speak Out Without Fear Fund. To address this, in the third year of the fund, Avon and ELAS jointly developed a set of behavioral indicators, such as the number of people engaged and affected, and public-policy-related indicators, such as the number of policies initiated or driven by the project.

Lessons Learned

The case study findings highlight the importance of co-creation of indicators and evaluation tools and the challenges in doing so. Because the size and nature of projects varied greatly, it was difficult to measure their impact with common indicators. Furthermore, it was challenging to establish indicators for behavior change, which often occurs slowly over time. By the third edition of the fund, however, the partners realized that they needed to align expectations about what could be measured during a project period, and subsequently developed indicators.

More broadly, the partnership between Avon and ELAS proved to be transformational—not simply a transactional funding relationship—because of the parties’ ability to work together to truly co-create the Speak Out Without Fear Fund. This required open minds, mutual respect, transparency, ongoing communication, and patience on both sides. In addition, because staff has changed at both institutions during the partnership period, it was important to have organizational buy-in for the partnership and ongoing sharing of information internally at Avon about the fund’s activities.

Amalia Fischer of ELAS remarked that the partnership built with Avon now goes much deeper than project funding and has helped ELAS develop new, meaningful relationships and networks. And Lirio Cipriani of Avon noted: “The partnership has enabled Avon to support solutions [to end domestic violence in Brazil] that are appropriate for the local conditions and, as a result, can lead to more profound and lasting transformation.”

Developed in Partnership with:

Reports | Thursday September 1, 2016

Responsible Luxury Initiative: Animal Sourcing Principles

This document sets out the general principles according to which all animals, both farmed and wild- caught, in our supply chains should be treated. The principles have been developed to take into account the diversity of animal products we source as well as the different regulatory environments in which animals…

Reports | Thursday September 1, 2016

Responsible Luxury Initiative: Animal Sourcing Principles

Preview

As companies in the luxury sector, dedicated to excellence in all areas, we are committed to responsible and sustainable business principles and practices, including sustainable sourcing. We work toward upholding such practices and principles throughout our own businesses as well as in our supply chains, by working with supply chain partners who share our values and approach to sustainable and responsible business. Since we may use material from animal origin, such as leather, animal fibers, exotic skins, and fur, in some of our products, we are deeply committed to principles and practices that require animals in our supply chain to be treated with care and respect, and for these species to be sustained, through sustainable trade, species conservation, and protection of ecosystems.

Blog | Tuesday June 14, 2016

Sustainability and CSR: A Word about Terms

What is CSR, what is sustainability, and why does BSR prefer to use one term over the other?

Blog | Tuesday June 14, 2016

Sustainability and CSR: A Word about Terms

Preview

If you came to BSR’s website looking for information on corporate social responsibility or to ask, “What is CSR?”, only to find a lot of talk about sustainability, you may be wondering why this is so and whether you’ve come to the right place (you have!).

So why does BSR focus on sustainability vs. CSR? And what’s the difference, anyway?

First, a quick qualifier: As a global nonprofit business network and consultancy, we take a flexible approach to the use of terms in our project work, reflecting the diverse needs and understanding of our members and partners in different parts of the world. In our experience, CSR, sustainability, sustainable business, corporate citizenship, and the like are all generally used to describe the same thing, and so we are happy to use whatever terms resonate most in a given place and context.

For purposes of our own branding and thought leadership, however, we see value in consistency and have made some clear choices based on what we are trying to achieve—and we recommend that our members do the same. In our case, the language of sustainability wins out over CSR for a number of reasons.

Sustainability conveys greater ambition because it focuses on what we need to achieve, rather than where we are today. The original definition of sustainable development, from the first Rio Earth Summit in 1992, focused on “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

The language and tools of CSR, at least in its early forms, tended to focus on meeting—or balancing—the needs of stakeholders today. Additionally, the term is often confused with philanthropy. As BSR and the broader field have come to focus more on long-term systemic issues, such as climate change and the inclusive economy, we felt that the ambition conveyed by sustainability better captures the objectives of our work.

Sustainability emphasizes a common agenda for all sectors of society, while the “C” in CSR calls out corporate practices more exclusively. BSR’s above-mentioned focus on critical systemic issues has come with a greater commitment to multistakeholder collaborative initiatives, in which business, government, and civil society all have critical roles to play.

Sustainability is a holistic concept that encompasses the full range of environmental, social, and economic issues addressed by our work. While the same is true of a good CSR strategy or program, the “S” in CSR is too-often construed to mean a narrower focus on social issues. That is also why we now go by “BSR” instead of our original moniker, “Business for Social Responsibility.”

Sustainability represents a concept that, in our experience, is more easily integrated into the core purpose of business than “responsibility,” which is often perceived as a check or counter-balance to business-as-usual activity. As the field has evolved from an exclusive focus on risk management and avoidance of harm to also encompass innovation and value creation, sustainability provides a more attractive and inspiring framing.

In short, “sustainability” reflects the ambition, reach, and inspiration required to achieve BSR’s mission of working with business to create a just and sustainable world. And although some may argue it’s just semantics, to us, sustainability—and what comes with it—is core to everything we do.

Case Studies | Wednesday March 30, 2016

Measuring the Net Positive Value of ICT in Online Education

Measuring the Net Positive Value of ICT in Online Education

Case Studies | Wednesday March 30, 2016

Measuring the Net Positive Value of ICT in Online Education

Preview

This case study, published by BSR’s Center for Technology and Sustainability, examines the the net positive impact of ICT in online education, using as the case study Arizona State University’s current ASU Online education program for undergraduate degrees.

Summary

As online education has evolved in the American undergraduate education system, the use of information and communications technology (ICT) has skyrocketed. Online-class delivery systems are becoming the norm, even in face-to-face classes, as have online course-management and advising systems.

This report focuses on the net positive impact of ICT in online education, using as the case study Arizona State University’s current ASU Online education program for undergraduate degrees.

The ASU Online study indicates that there are both environmental and socioeconomic benefits to the use of ICT in online education.

Online education makes high-quality degrees accessible to a larger and more diverse group of people, many of whom would not otherwise earn a degree. Because these degrees are more accessible and affordable, they create positive socioeconomic impacts through increased incomes, greater productivity, and improved social conditions; we conservatively estimate the total socioeconomic impact to be US$545,000 per undergraduate degree. Positive environmental impacts result primarily from reduced student and faculty travel as well as avoided classroom construction, equaling an estimated carbon savings of 33.2 metric tons for that same undergraduate degree.

The ASU Online study suggests that ICT also enables innovation in education that can be scaled nationally and globally, satisfying the overwhelming need for access to education in developed, emerging, and developing countries.

Measuring the Environmental Benefits of ICT and Online Education

ASU Online was established to provide improved access to its educational offerings while also providing a new revenue stream for the university at a time when it faced reduced state and federal funding. However, the ASU Online campus has evolved to be a critical component of ASU’s sustainability plan: It plays a key role within ASU’s broader sustainability strategy, which includes climate neutrality, zero waste, zero wastewater, and low hazardous-material goals. The university continues to aggressively pursue these goals, including net zero energy by 2030, so ASU has made measuring environmental benefits a requirement across the university.

The Assessment Process

This report was prepared by ASU sustainability scientists from the university-wide Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability, including the W.P. Carey School of Business, the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, and the Global Sustainability Solutions Services of the Walton Sustainability Solutions Initiatives, with both intellectual and financial support from Dell.

In order to assess the net positive impact of ICT at ASU Online, the research team developed high-level models of variables and populated them through structured interviews of key stakeholders and ICT platform experts across the education landscape, with a focus on Arizona State University and ASU Online. In addition, we conducted a literature review of published studies in areas relevant to net positive assessment of online education. We used delivery and completion of undergraduate degrees as the unit of analysis.

Because net positive is a relatively new concept, it was difficult to find any studies during our literature review that explicitly studied online education from this point of view. Instead, we focused our search terms on the various aspects of online education that create value or positive impacts to society.

The Net Benefits Model

Study Scope

For the purposes of this study, ASU means the entire ASU enterprise, consisting of 18 schools and colleges, five physical campuses, and the ASU Online virtual campus. ASU Immersive is used to describe the historic campus-based ASU, while ASU Online describes the unit that manages ASU degree programs through the ASU Online platform.

For the purposes of this case study, we view this greater ASU enterprise as a system that takes in enrollees, uses energy and other resources as inputs, and then produces outputs such as graduates and negative environmental impacts. Graduates, in turn, create positive socioeconomic impacts and outcomes. Increasing the number of graduates while reducing resource consumption enhances ASU’s overall net positive sustainability goal. ASU Online plays a critical role in achieving ASU’s overall sustainability goals.

Models and Metrics

Interviews and literature review provided the content for the development of two models and two key areas for output metrics: the holistic value proposition and the dynamic view of ASU Online through 2030.

Holistic Value Proposition

Any business model results in a specific set of benefits to stakeholders. This bundle of benefits—the value proposition—can be characterized for all stakeholders in the value network. This distribution of value capture is referred to as the Holistic Value Proposition (HVP) (O’Neill et al., 2006). The HVP for this study included 20 interviews of internal and external experts from the following stakeholder groups: broader society, online students, academic institutions offering online education, faculty, employers, and experts from the ICT industry.

A Dynamic View: ASU/ASU Online 2015-2025

Education innovation and its impact on the sustainability of higher education at ASU, which we measure in this section, is scalable both nationally and globally. In the ASU case, the net positive position of ICT in online education is primarily due to avoided carbon plus the positive socioeconomic impact of education access and affordability. Many more people will attain a degree through ASU than would have without online access.

Using a somewhat idealized best-case scenario of the ASU complex if it meets its growth and operational sustainability goals, the study determined that by 2025 ASU will be educating 100,000 students through immersive courses and 100,000 online, with nearly 75 percent of the total student body taking some portion of their classes online. This will have the net effect of producing more graduates for a much lower environmental footprint than today, and the use of ICT will be a key driver.

The big impacts at a national level are the economic and social returns of a degree, which we document in the next section of this report. The longer-term net positive story is one of innovation in a dynamic global market with its overwhelming need to educate students in developed, emerging, and developing countries. Online education may be the only hope for 9.5 billion people to get a high quality education in the coming decades.

Socioeconomic System-Wide Effects

Access to and completion of an online undergraduate degree program offers a number of social and economic benefits.

A key finding of this study, supported by the interviews, is that many ASU Online students would not get a degree at all if an online degree were not available. Access to education is one of the biggest contributions of ASU Online. Hout (2012) argues that the societal gain increases when more people are educated. If education boosts collective as well as personal productivity, then increased educational attainment for a population might be a key causal factor in overall economic growth—in fact, estimated social returns due to education might exceed individual returns. Lange and Topel (2006) observed this trend in metropolitan cities.

Ellwood & Jencks (2004) found that college graduates are less likely to go through divorces than those who have no degree. A number of studies have suggested that college education improves a person’s general health (Mirowski & Ross, 2003). Although causality is difficult to prove, a general argument made by many studies is that formal education improves a person’s understanding of the qualities and habits that promote good health.

Although there have been no attempts to establish causal linkages between education and happiness, Yang (2008) showed that people with a college degree are happier than those without a college degree.

The ASU Online Handprint and Footprint Model

In developing this report, the research team used the Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI) methodological framework as a guide to develop the carbon-focused environmental aspects, or footprint, of the net positive statement. We also considered using the framework to express the socioeconomic benefits, or its handprint. The research team will provide the report data in GeSI, along with observations on its applicability to this type of net positive analysis, in the near future.

When it comes to assessing the net positive impact of ASU Online, key factors included in the scope of the model are the net ICT footprint of ASU Online and the potential social and economic handprint of students that online access enables to complete a degree.

The model quantifies handprint by including the expected additional average lifetime economic earnings after attaining a bachelor’s degree, adjusted for a shorter remaining career span, and potential higher net worth at retirement. Potential benefits are based on reported research findings regarding the lifetime value of completing an undergraduate degree compared to not completing the degree. We consider broader social returns largely in terms of avoiding and/or contributing social services. We conservatively estimate the net positive socioeconomic impact per degree to be US$545,000. The model also identifies the overall system-wide social impacts of attaining a college degree.

For the footprint, the model focuses on quantifying carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) emissions. Other environmental impact categories such as paper reduction, water use, and building construction were only briefly considered during this study and we made no attempt to formally quantify them. The factors we used to calculate the footprint in this study include increases in direct ICT emissions, net new data center construction and ICT equipment, telecommuting savings, and reduced construction and use of campus facilities. The net positive impact on emissions is conservatively calculated to be 28.3 metric tons of CO2e per degree produced.

The ratio of the positive benefits of producing a college graduate to the resources required to do so, including emissions, is growing larger quickly due to the maturation of online education and the dedication of higher-education institutions to making it so. ICT plays a central and critical role.

Limitations and Gaps, Future Research

During this research, we identified six significant limitations of the ASU Online study, and suggest next steps for future research.

The increased investment in ICT systems to accommodate online study and the increase in greenhouse gas (GHG) production from added ICT systems for online study are not thoroughly identified in this study. Next steps in a follow-up research project would include gathering and analyzing appropriate samples of use data.

The quantification of GHG savings from reduced campus infrastructure needs makes an assumption about the annual operating savings as a percentage of the reported GHG impact of the campus and a very high-level estimate of the net benefits from classroom construction avoidance. Steps in a follow-up research project would include validating the assumptions stated above for both operational and construction scenarios.

Initial findings on enabling the completion of a degree are based on a limited sample of cohorts that started the ASU Online undergraduate degree and interview information gleaned from ASU experts. A follow-up study might use a survey or structured interviews to gather more complete information about the demographics and perceptions of the student base in the ASU Online degree programs. Additional and larger cohorts could also be added.

Initial suggestions about lifetime income and lifetime social impacts are based solely on the many continuing studies of the impact of completing a college degree compared to only having some college courses completed. Although existing sources of data for these handprint economic and social factors may prove to be adequate, a follow-up study would explore these sources in greater depth.

This is a single case study. It will be hard to generalize to a broader base at a national level without conducting some additional case studies and/or gathering a limited set of data for a larger sample of universities. This should be done in a follow-up study.

Other environmental factors briefly discussed during this study and then excluded from it include water use on campus, solid waste disposal from campus to landfill, water runoff and sewage waste from campus, and food supply chain issues.

Conclusion

The contribution of ICT and ASU Online to the net positive position of the ASU complex is substantial and based almost entirely on increased access to and affordability of undergraduate degrees. At the same time, it is lowering the environmental footprint required to produce those degrees.

The important point is that ICT is enabling innovation in education in general and in online education specifically. The ratio of the positive benefits of producing a college graduate to the resources required to do so, including emissions, is growing larger quickly due to the maturation of online education and the dedication of higher-education institutions to making it so. ICT plays a central and critical role.

For complete data analysis and access to report appendices, download the report or view the ASU Online "how it works" page.

Case Studies | Wednesday March 30, 2016

Looking Under the Hood: ORION Technology Adoption at UPS

Looking Under the Hood: ORION Technology Adoption at UPS

Case Studies | Wednesday March 30, 2016

Looking Under the Hood: ORION Technology Adoption at UPS

Preview

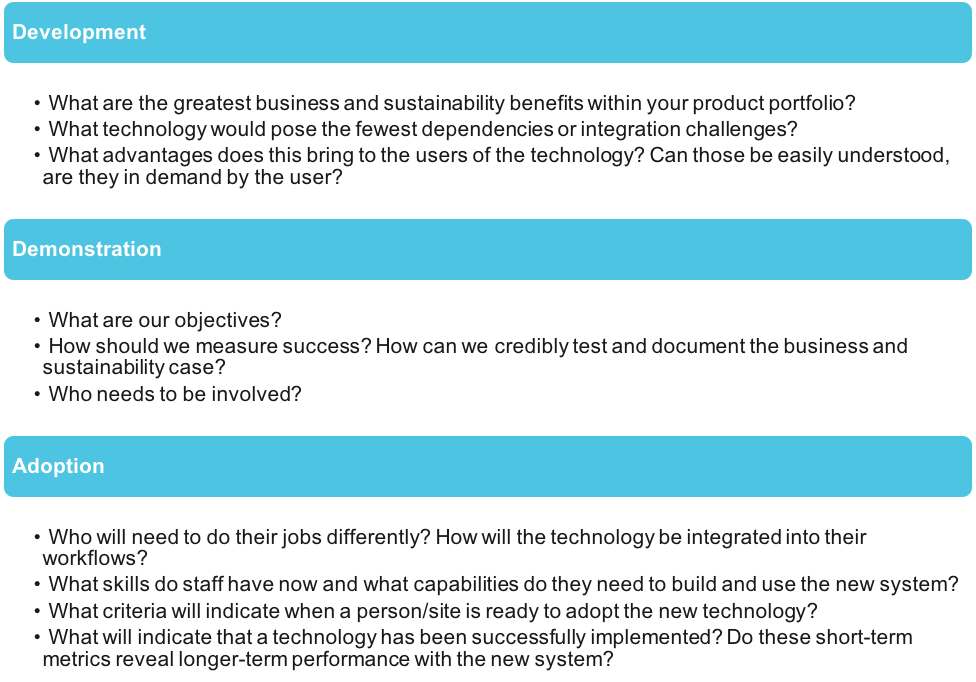

This case study, published by BSR’s Center for Technology and Sustainability, examines UPS®’s deployment of ORION, a route-optimization software program for its drivers, and focuses primarily on the challenges related to technology adoption, from development to deployment.

Across industries, information and communications technology (ICT) has great potential to address some of the world’s most complex global environmental and social challenges. Even where good technology exists, however, there remains a key challenge related to adoption: selecting and installing a solution, integrating it within existing systems, and ensuring successful uptake by users to verify that the technology delivers on its promise.

New technologies often require new business processes, and even if those processes promise greater efficiency, cost savings, and/or other improvements, they also require behavior change—and change is hard.

Delivering on Sustainability Solutions: From Idea to Action

A Center for Technology and Sustainability Framework

To develop this case study, BSR conducted interviews with UPS staff along with background research on the objectives and attributes of the ORION system. We hope that this case study will help other companies successfully implement technology-based sustainability solutions through a change-management framework that takes into consideration design, process, and people.

The Opportunity

Developed by UPS, ORION—or On-Road Integrated Optimization and Navigation—is a route-optimization system that analyzes a collection of data points including the day’s package deliveries, pickup times, and past route performance to create the most efficient daily route for drivers.

UPS created ORION as part of a broader effort to use data and predictive models to increase efficiency, thereby reducing both costs and environmental impacts. By charting more efficient routes, UPS was able to maximize the utilization of delivery vehicles and drivers, resulting in significant fuel savings—one of UPS’s largest costs.

ORION is expected to reduce operating costs by US$300 million to US$400 million a year once it is fully implemented in the U.S. in 2017. More than 70 percent of the company’s 55,000 U.S. routes are now using the software, with an average daily driving reduction of between six and eight miles. To put this into perspective, UPS can save US$50 million a year by reducing by one mile the average aggregated daily travel of its drivers.

Specific Change-Management Challenges for Orion

To achieve maximum cost and emissions reductions, UPS had to ensure uptake at several different project stages, each with its own unique change-management challenges:

- Development: R&D leads were asked to design a technology solution that worked better than existing practice and to prove to business leaders that the approach had potential.

- Demonstration: Prototype testing and business-case validation. Prototypes developed in the lab were then tested in the field, first for smaller and then for larger groups of UPS drivers.

- Adoption: Operationalizing and rolling out. Convincing thousands of UPS employees to embrace integration of ORION into their day-to-day work.

UPS's Approach

Implementing ORION took place in three major phases:

- Development: The Idea

UPS started developing ORION in 2003, with the aim of layering predictive algorithms on top of UPS’s existing package and vehicle tracking systems. The development took place within the Operations Research and Advanced Analytics groups, starting with a small, diverse team: a PhD in operations research, an industrial engineer, a UPS business manager, and several software engineers.

UPS combined well known software algorithms for optimizing routes with existing business rules (such as package delivery order), but initial results were frustratingly inconsistent and not easily implementable by UPS drivers. The ORION team challenged conventional wisdom and developed a set of new rules to guide their routes. Once ORION started to produce efficient results, UPS business leaders were invited to view ORION in action so they could witness first-hand the differences between a typical driver’s route and an ORION route.

- Demonstration: Testing and Validation

Next, UPS wanted to demonstrate consistent results. Once it was clear that ORION would work in a lab setting, the team tested the program for an entire operational location and showed that efficiency significantly improved. This was then repeated in two more operational locations, and then in another eight. By then the team had expanded from five to approximately 30 people. The testing and validation at each stage enabled the buy-in and resources for further expansion. The key focus of the analysis shifted from “is there a benefit?” to “how do we scale?”

- Adoption: Operationalization and Deployment

In the final stage of adoption, UPS developed a scalable software tool and then deployed this tool across the organization. The key challenge here was to inform and motivate UPS staff across the company to adopt this new system. The ORION team has grown from 50 people at the software-development stage to more than 700 people today—the majority of whom are in the field working on technology deployment.

Because UPS knew that the technology development would take significant time, the IT team developed a “hardened prototype” to start deploying even while full software development was still underway. This enabled UPS processes to integrate ORION into daily staff workflows.

At this stage UPS also faced its most significant change-management challenge: Many people didn’t believe that a computer-generated algorithm could be an improvement over decades of driver experience. Making this case involved education, communication, and follow-up, but most importantly a change in how drivers and their managers measured success.

Results: Seeing the Impact

The successes UPS has seen as a result of implementing ORION support the many years of effort that have gone into its development. The company has already seen an average daily reduction of six to eight miles per route for drivers who are using ORION routes. This reduction has already made significant reductions in fuel use and vehicle emissions.

And when ORION is fully implemented throughout the U.S. in 2016, UPS expects to see annual reductions of 100 million miles driven and fuel savings of 10 million gallons per year. These add up to 100,000 metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions avoided every year.

The Evolution of Analytics at UPS

Over the past several decades, UPS has expanded its decision-making capabilities using data and modeling tools, starting first with descriptive analytics and continuing to predictive and then prescriptive analytics.

Descriptive analytics help you understand what is happening now and what has happened in the past. For UPS, this includes identifying and tracking packages using sophisticated labeling called Package Level Detail. This allows UPS and its customers to track packages as they flow through the delivery system. Descriptive analytics at UPS also include collecting detailed truck telematics data that is analyzed to further support timely preventive maintenance of its fleet.

Predictive analytics allow you to use past data to identify where you will be in the future. For example, using historical package data, UPS can predict future package volumes. This allows UPS to match capacity with demand and better automate the package-delivery process. These Package Flow Technologies save UPS more than 85 million miles driven per year.

Prescriptive analytics go beyond making forecasts to recommending specific courses of action. ORION, with its daily recommendations for driver routes, is an example of prescriptive analytics. Because prescriptive analytics can make different (and sometimes counterintuitive) recommendations for action, change management is particularly important to ensure people trust the system.

Lessons Learned

New Technology Can Mean New Ways of Running the Business

In order to capture the full value of a new technology solution, one must think differently about the business. Because UPS had a long tradition of working in a particular way, it was challenging at first to implement a technology tool that would require a fundamentally different approach to drivers’ routes.

Indeed, when ORION was first being developed, R&D staff struggled to make it work. Developers tried to stick to the prescribed rules that the business had developed over time, but this resulted in an unworkable software algorithm that drivers couldn’t follow. When the developers took a broader perspective and re-examined driver best practices, they were able to develop a version that produced “drivable” results.

The benefits of technology-based sustainability solutions often seem straightforward—reducing miles traveled through more efficient route planning, for example. But realizing that potential requires that we re-think many other supporting systems and activities—for example, how drivers are trained and how they are measured and rewarded—in ways that can be counter-intuitive.

"With technologies that are transformational—like ORION—you have to be willing to let go of your exisiting business paradigms. You have to start with an open mind about how the technology can change the business." — Jack Levies, Senior Director of Process Management, UPS

Plan For and Invest in Implementation

With ORION, UPS found that testing and deployment represented more than 75 percent of the total cost of the project. Successful companies plan for this from the start, investing the funding, staff time, and expertise to scale. In addition, part of UPS’s vetting process for ORION was assessing whether they could easily train staff on the new system and see consistent improvements over time. For large technology systems, companies should include iteration and testing not only in product development, but also in implementation and rollout.

Even with Obviously “Sustainability-Driven” Technologies, Lead with the Business Case

With ORION, UPS’s business outcomes and sustainability outcomes were inextricably linked. Every mile driven correlated not only to reductions in miles driven, but also to reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. What ensured internal support, however, was the financial case, demonstrated through pilot testing. Sustainability advocates should always lead with a strong business rationale for any new technology, even for approaches that create obvious social and environmental impact. Without this, it will be difficult to attract the internal resources to scale.

The Technology Must Be Easy to Explain

Because ORION is based on a new kind of predictive model, it may recommend route scenarios that—while more efficient—are highly counter-intuitive for a driver. Especially at the beginning of ORION’s deployment, the UPS team paid special attention to having every aspect of the system be easily understandable by drivers. This ensured that the operations teams understood how the system worked and why it did what it did, which enabled them to see when and how it provided more efficient solutions. As drivers have become more familiar with ORION and have learned to trust its recommendations, the team has been integrating even more sophisticated and efficient optimizations that are even less intuitive.

Assessment Metrics Must Align

One challenge that UPS experienced early on in the deployment of ORION was significant drops in performance once the deployment team left a site. The core issue was that the operations teams were using old approaches to measure performance. Before ORION, drivers compared themselves against past performance on each route; if they performed better than previous months, then that was a success. With ORION, however, it became possible to compare performance against an ideal route and achieve significant new efficiencies by comparing performance against this best practice. This required adopting new ways to measure performance at each ORION site.

UPS also needed to develop short-term metrics to determine whether an ORION deployment had been successful at a particular site. Actual performance is difficult to measure over the course of just a few weeks, so UPS developed leading indicators—like the percentage of time a driver follows an ORION route—to enable success measurement during deployment. Through iteration, UPS selected short-term metrics tied to longer-term indicators of success, such as cost reductions and performance over time.

Prototypes Make the Opportunity Real

To demonstrate the technology’s potential, R&D staff took decision makers on what they called an ORION ride. Using a rental car, they took a test drive of the UPS route, guided by prototype ORION software. This demonstrated the potential of the ORION technology by allowing operations teams and drivers to witness how it worked and how it could improve on existing approaches. In particular, these rides helped UPS employees see how software algorithms, even if occasionally counterintuitive—like passing a house on an initial visit to the neighborhood only to revisit it to deliver a package later—could result in better efficiency overall.

More Sophisticated Software Systems Require Better Data

With software systems, the output is only as good as the data input. UPS found that available maps weren’t accurate enough to serve as a basis for ORION. As a result, part of any ORION deployment involves validating maps and other supporting data. UPS also conducts ongoing monitoring of data quality and has processes for addressing data inaccuracies. Any company transitioning to predictive algorithms should expect to invest significantly in the underlying data.

Deploy Slowly at the Start to Achieve Greater Scale

UPS started its deployment slowly at the beginning to ensure that the concepts were being trained effectively and that the deployment approach was successful. The company found several early ways to improve—for example, in how they measured the short-term success of the deployment and linked this to longer-term success—which they were able to incorporate. This ensured success at a critical time, when skepticism of the new approach was highest and before results had been demonstrated on a large scale.

Integrate With Existing Work Processes

To be successful, technology tools need to fit inside the processes that people already follow. This requires on-the-ground work, interviews with users, and lots of testing. Indeed, site managers and delivery drivers were integral parts of the ORION development team from the start, since they were able to provide feedback on what actually works in practice.

Looking Forward

To achieve the business and societal transformations needed for long-term sustainability, new technologies and approaches must be integrated into how we do business. To help companies successfully implement technology-based sustainability solutions, the Center for Technology and Sustainability poses the following questions to help business leaders navigate successful implementation of technology solutions.

Case Studies | Wednesday March 30, 2016

Measuring Environmental Benefits of Health Information Technology

Measuring Environmental Benefits of Health Information Technology

Case Studies | Wednesday March 30, 2016

Measuring Environmental Benefits of Health Information Technology

Preview

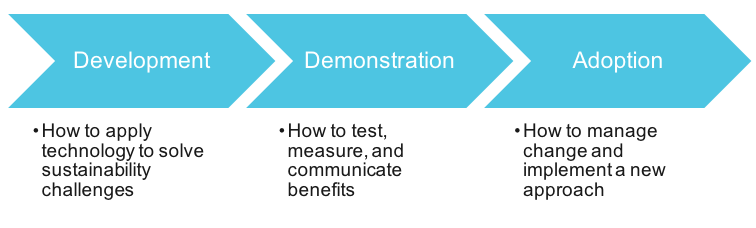

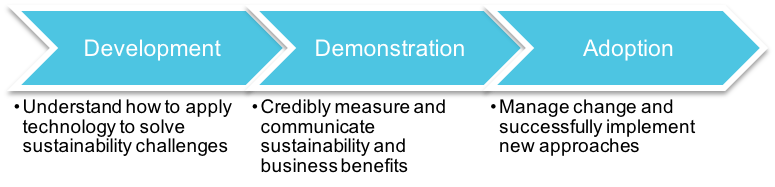

This case study, published by BSR’s Center for Technology and Sustainability, examines the environmental benefits and impacts of health IT. Through case studies, the Center for Technology and Sustainability helps companies understand how to apply technology to solve sustainability challenges, credibly measure and communicate sustainability and business benefits, manage change, and successfully implement new approaches.

Summary

The introduction of information technology (IT) into a healthcare context continues to radically shift how healthcare is delivered. Patients today expect to be able to communicate with their doctors virtually and to do many of the healthcare tasks online that previously took place in person, such as answering questions, refilling prescriptions, and more. On the healthcare-delivery side, health IT enables the integration of patient records, providing ready access to information for doctors and patients alike.

In addition to the obvious health benefits, research to date shows that health IT can lessen environmental impacts by reducing the need for patient transportation and by reducing the amount of paper used in medical records. In turn, the electronics used in health IT use energy, create waste during manufacturing and end-of-life, and contain a variety of potentially hazardous chemicals and materials.

Approach

The Center for Technology and Sustainability supports the development, demonstration, and adoption of technology-based sustainability solutions for a variety of industries.

This case study focuses on technology demonstration, by reviewing and adding to work done by Kaiser Permanente (Kaiser) on the environmental impacts of its electronic health records system. Work to measure the net benefits of IT in electronic health has been limited to date, with Kaiser conducting the first major study in this area.

This case study was based on interviews with Kaiser staff, BSR analysis, and published material related to Kaiser’s activities as well as the broader benefits IT brings to healthcare. With this study, the Center for Technology and Sustainability aims to advance the measurement of environmental impacts and benefits from health IT. With better sustainability measurement, companies in the healthcare sector will be able to make decisions about technology not only based on business impacts, but also on the ability of this technology to drive social and environmental benefits. In addition, companies in the technology sector will be able to quantify the environmental impacts of their healthcare technologies.

The Opportunity

Because Kaiser Permanente was an early adopter of electronic health records (EHR) and health IT, the company has already addressed questions other companies are only now facing about the net environmental benefits of such systems. It was clear to Kaiser staff that electronic records reduce the need for paper use, but the members of Kaiser’s Environmental Stewardship Council wondered whether this benefit would be offset by potential negative environmental impacts from increased computer use.

Kaiser’s decision to invest in health IT was made based on rigorous business assessment and a quantitative evidence base. An understanding of the social and environmental impacts was one part of understanding the total cost of these systems.

Kaiser employees undertook a quantitative study to understand these environmental impacts, working with staff throughout the organization and in partnership with Kaiser’s Environmental Stewardship Council.

Because no previous studies of this type had been conducted on health IT, Kaiser developed the model for assessing net environmental benefits over approximately one year, including model development, data collection, internal review, and external review. One staff person led the work part-time, with some additional assistance for field work (such as measuring the weight of charts) and analysis.

Kaiser then published the findings of this study in the journal Health Affairs, in order to help others understand the net benefits of health IT and, if desired, apply Kaiser’s approach to their own organization. This case study focuses on the business impacts of this work and updates the analysis for 2015.

The positive environmental benefits of EHR included avoided paper use, avoided patient transportation, avoided chemical use, avoided plastic waste from x-rays, and avoided water use. The study also highlighted a number of negative environmental impacts such as increased energy use, increase in plastic waste, and an increase in chemical waste.

The study found that, by far, the biggest positive environmental benefit of health IT was the fact that patients needed to take significantly fewer vehicle trips to the doctor’s office. On the other hand, the biggest negative environmental impact came from the increased energy use from computers and electronic systems.

Business benefits seen from the integration of health IT include reduced expenditures on paper use, records transportation, and chemical purchase and disposal. Additional financial savings, such as reductions in patient transportation, are not captured within the Kaiser system but are enjoyed by patients.

Kaiser’s Approach

Measuring the environmental benefits of a particular technology is a three-step process:1

- Define Scope

- Prioritize Impacts

- Conduct Assessment

1. Define Scope

As an initial step, it is important to identify the purpose and scope of the study. The business processes impacted by the use of information technology must be assessed, along with a qualitative review of the environmental implications of these changes.

To assess the environmental impact of EHR, Kaiser identified four focus areas: (1) reductions in paper use, (2) changes in patient travel, (3) increased use of personal computers and data centers, and (4) changes in x-ray use (from chemical to digital processing).

There are a number of different frameworks used for defining the environmental priorities and impacts of healthcare, including the Global Green and Healthy Hospitals Agenda, Practice Greenhealth’s Eco-Checklist, and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board’s Health Care Standard. Environmental issues that these frameworks identify as most relevant for the healthcare sector include chemicals, waste, energy, water, transportation, food, and green building. Kaiser used the Eco-Health Footprint, a 2009 report outlining the major impacts associated with healthcare.

2. Prioritize Impacts

An important part of any modeling exercise is determining what to include and what not to include either because data is not available or because the impacts are not significant when considered relative to other aspects of the model. There is often limited data available, especially in early stages of developing an environmental-impacts model, so it is important to start with the most significant impacts.

Kaiser’s study focused on the impact of EHR in four environmental impact areas: (1) greenhouse gases, (2) toxic chemicals, (3) waste production, and (4) water use. Kaiser excluded two environmental impact areas—the use of land for buildings and the emission of air pollutants like ozone, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide—in order to focus on the four largest and most direct environmental impacts connected to the use of electronic health records.

3. Conduct Assessment

The final step in the model is to quantify the environmental costs and benefits of each business-process change through a combination of primary and secondary data. This should include the documentation of any assumptions made and key areas of uncertainty. Most importantly, it is crucial to assess what decisions can be made or changed as a result of the analysis.

Lessons Learned

Benefits Depend on Application

One of the most significant findings of Kaiser’s work is that the net environmental benefits of health IT depend significantly on how the organization uses the technology. A system like EHR can be used as a straight one-for-one substitution for paper use, or it can enable significant changes to delivering patient care. Also, an organization like Kaiser Permanente has several opportunities for using EHR for integrated care than would a stand-alone doctor’s office.

The Biggest Benefits Come From Rethinking the Business

If a technology enables significant transformations in how the business is operated or its services are delivered, the environmental benefits can be very large. Instead of thinking of technology as a one-for-one substitution of computers for paper-based records (which represents some modest savings in paper), Kaiser found when they thought more broadly about the transformative role of technology, they found the biggest environmental benefits. For example, adjusting business processes so that patients could interact with doctors online reduced the number of patient vehicle trips. For companies looking to apply technology, understanding the new business processes that the technology enables is a great place to start.

Concrete Measurement Improves Decision Making

This assessment helped Kaiser staff better recognize the environmental impacts, both positive and negative, of its technology decisions. Cost and quality of care are the dominant drivers of its IT systems, but a full understanding of environmental impacts helped increase awareness about these issues within the organization and gave staff a basis on which to make decisions. For example, all patients receive an after-visit summary; after assessing the environmental impacts, Kaiser provided an option for patients to receive this electronically instead of in printed form.

Assessment Requires Both Secondary and Primary Data

Much of the data used in the study already existed in the public domain. However, one challenge in conducting the study was identifying methods to obtain some key source data, such as avoided paper use and avoided patient transportation. These required the collection of primary data, including the number and types of IT equipment, the weights of paper charts, the average distance between Kaiser facilities and patient residents, and more. In addition, Kaiser had published several previous studies on the impact of EHR on the number of in-person patient visits; we used these studies as part of the analysis.

As healthcare is increasingly offered virtually, we will see further environmental benefits, such as a reduced need for clinical space and an even further reduction in patient transportation.

Looking Forward

There are two major focus areas to consider for future measurement efforts. First, computers today have lower energy use and environmental impacts than they did in 2011, when the study was conducted.

Second, there is an opportunity to expand the analysis to include other significant impacts of health IT. Aspects that were not included in Kaiser’s initial model, but which may create environmental and other benefits, include the potential to reuse floor space previously utilized for storing paper records, as well as reductions in vehicle use to transport records from site to site. The lack of paper records, for example, means that storage rooms no longer need to be heated and cooled, and being able to reuse space could potentially delay the need for additional building construction.

It is clear that the future of healthcare includes significant technology-based solutions. There is hardly an aspect of healthcare that hasn’t changed as a result of health IT, starting with electronic records but extending far beyond. As healthcare is increasingly offered virtually, we will see further environmental benefits, such as a reduced need for clinical space and an even further reduction in patient transportation. Future assessments of environmental benefits from health IT should look at these wider, more systemic impacts, especially as healthcare organizations become more integrated in the face of a changing business environment and regulatory models.

1Adapted from Global e-Sustainability Initiative (2010), “Evaluating the carbon-reducing impacts of ICT: An assessment methodology.”