Searching for:

Search results: 261 of 1137

Sustainability FAQs | Tuesday November 1, 2022

Materiality and Salience

This FAQ sets out the BSR perspective on the related concepts of materiality and salience. We believe that implementation of the key concepts described in this FAQ—such as double materiality, impact materiality, and salience—provide the foundation for more resilient business strategies, informed decision making by all stakeholders, and the realization…

Sustainability FAQs | Tuesday November 1, 2022

Materiality and Salience

Preview

This FAQ sets out the BSR perspective on the related concepts of materiality and salience. We believe that implementation of the key concepts described in this FAQ—such as double materiality, impact materiality, and salience—provide the foundation for more resilient business strategies, informed decision making by all stakeholders, and the realization of human rights in practice.

Materiality

What is materiality?

Materiality is a foundational concept underpinning corporate disclosure.

The concept of “materiality” has its origins in the field of financial reporting, where it has referred to the disclosure of financial and non-financial information that is useful to the decision making of investors, lenders, and other creditors. These disclosures have generally been a legal requirement.

The term “materiality” was subsequently adopted by the field of sustainability[1] reporting, where it has referred to the disclosure of information that is useful to the decision making of a wider range of stakeholders, such as civil society organizations, policy makers, and communities. These disclosures have generally been a voluntary undertaking.

BSR typically uses the following two definitions of materiality in the context of sustainability disclosures, with the IFRS representing the investor-oriented test and GRI representing the wider stakeholder-oriented test:

- IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standard General Requirements (IFRS S1): “Information is material if omitting, misstating, or obscuring that information could reasonably be expected to influence decisions that the primary users of general-purpose financial reporting make on the basis of those reports, which include financial statements and sustainability-related financial disclosures and which provide information about a specific reporting entity.”

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI): “Topics that represent an organization’s most significant impacts on the economy, environment, and people, including impacts on their human rights.”

It is important to note that the IFRS definition is conceptually consistent with the SEC definition of materiality, which defines material issues as matters that “either individually or in the aggregate, are important to the fair representation of an entity’s financial condition and operational performance…[information that is] necessary for a reasonable investor to make informed investment decisions.”

BSR also utilizes definitions contained in the draft European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) being developed to accompany the new EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). These are conceptually consistent with the IFRS and GRI definitions:

- Financial materiality: “A sustainability matter is material from a financial perspective if it triggers or could reasonably be expected to trigger material financial effects on the undertaking. This is the case when a sustainability matter generates or may generate risks or opportunities that have a material influence, or could reasonably be expected to have a material influence, on the undertaking’s development, financial position, financial performance, cash flows, access to finance or cost of capital over the short-, medium- or long-term.

- Impact materiality: “A sustainability matter is material from an impact perspective when it pertains to the undertaking’s material actual or potential impacts on people or the environment over the short-, medium- or long-term…”

What is “double materiality”?

Over the past two decades the concept of “materiality” has suffered from being one term with two different definitions—the legal requirement to disclose information relevant for investors, and the voluntary expectation to disclose information relevant for a wider range of stakeholders.

The ESRS have introduced the concept of “double materiality”. This provides clarity that companies should report on matters that influence enterprise value (financial materiality) and matters that affect the economy, environment, and people (impact materiality).

Today BSR typically takes a “double materiality” approach by incorporating both dimensions into a single materiality assessment, with one axis in a 2x2 being dedicated to each dimension.

This is consistent with the notion that double materiality is the union of the two concepts in their totality, and not simply examining where they overlap—i.e., double materiality is using both concepts in combination, rather than only considering their intersection. A sustainability matter is “material” when it meets the criteria defined for impact materiality or financial materiality, or both.

We believe that “double materiality” supports conceptual clarity (i.e., that some information is required by investors to assess the creation of enterprise value, and some information is required by other stakeholders to assess broader impacts on society) and works with the grain of standards development (i.e., it encompasses both the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards and GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards).

What is “impact materiality”?

The term “impact materiality” captures the notion that companies should understand the materiality of matters that affect the economy, environment, and people based on a company’s actual and potential impacts, rather than perceptions of what is important. The term “impact materiality” becoming increasingly common implies changes in how stakeholders are defined and how matters of importance are identified and prioritized.

In the past, materiality assessments often defined stakeholders as those whose judgments, decisions, and actions may be influenced by the company’s sustainability disclosures; material matters were those that were “of interest” and “decision-useful” for report readers.

By contrast, “impact materiality” defines stakeholders as those that have an interest that is (or could be) affected by the company’s activities and decisions, even if they are not users of a company’s sustainability reporting. “Impact materiality” determines material issues based not on whether they are “of interest to stakeholders”, but whether they “have an impact on the economy, environment, and people.”

What are the practical implications of “impact materiality”?

There are two main implications: (1) which stakeholders are engaged with, and (2) the criteria used to prioritize sustainability matters.

First, it is important for the company to engage with all affected stakeholders to understand how they may be impacted by company activities, and not limit stakeholder engagement to just those who regularly interact with the company—for example, this may mean paying closer attention to rightsholders that do not buy or use a company’s products, or to communities who may be impacted by infrastructure development.

Second, it means prioritizing impacts on the economy, environment, and people using the following criteria:

- Scale: How grave is the negative impact, or how beneficial the positive impact?

- Scope: How widespread would the positive or negative impacts be?

- Remediability[2]: Is it possible to counteract or make good the resulting harm (i.e., restoring the environment or affected people to their prior state)?

- Likelihood: What is the chance of the impact happening?

In practice, “impact materiality” means not asking stakeholders to “rank” how important they believe issues to be, and instead acknowledging that material impacts may not always be the most referenced concerns in stakeholder dialogue. Determining priorities is not a popularity contest.

What is “dynamic materiality”?

The concept of “dynamic materiality” captures the notion that the relative materiality of a sustainability matter may change over time.

One example is a sustainability issue initially being deemed as not having a material relevance for users of general-purpose financial reporting, but as having a material impact on the economy, environment, and people. Over time, this sustainability issue may become more material to users of general-purpose financial reporting, for example because of government regulation, evolutions in consumer sentiment, or changes in the operating context. The reverse can also happen if a sustainability matter is well managed by a company.

In this sense, the “impact materiality” component of “double materiality” can provide an early warning signal for what might become financially material later. It may also focus the attention of policy makers seeking to understand which sustainability matters are not material to enterprise value creation but are to society more broadly, and that therefore may benefit from greater regulatory attention.

BSR addresses “dynamic materiality” in part through our use of futures methodologies and scenario planning to identify how the materiality of issues may shift over time.

Do internal stakeholders have insights to offer on impact materiality?

Yes. In the past, materiality assessments often involved asking internal stakeholders which sustainability topics are most important for enterprise value creation and asking external stakeholders about which issues might influence their judgements and decisions.

However, internal stakeholders may have significant insights to offer on impacts on the economy, environment, and people—a product manager in a technology company may have insights into new product features that an external stakeholder would not, for example. The reverse can also be true, such as external stakeholders providing early insights into regulatory change or shifting consumer expectations.

Is anything changing in methods to assess “financial materiality”?

BSR anticipates greater discipline in assessing the impact of sustainability on enterprise value creation and enhanced alignment with enterprise risks management processes. For example, BSR’s methodology seeks to identify sustainability topics that may significantly affect enterprise value by influencing future cash flows or creating risks and opportunities for the company using an approach based on enterprise risk management, such as in our choice of assessment criteria. This might include:

- Strategy and financials: How significant is the impact on the company's ability to meet strategic and financial objectives?

- Reputation: How significant is the impact on the company's reputation?

- Regulation: How significant is the impact of the topic on the company's ability to comply with regulations?

- Likelihood: How likely is the impact to occur?

Further, it is important to note that, by focusing on enterprise value creation over the short, medium, and long term, the concept of financial materiality for sustainability reporting is different from the concept of materiality used in the process of determining which information should be included in a company’s financial statements.

Does BSR support use of the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)?

Yes. BSR welcomes the fact that the ISSB and ESRS standards will build on existing frameworks and guidance, including the TCFD Recommendations and Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) Framework.

[1] We define sustainability in its broadest sense, encompassing the economy, environment, and people, including social justice and human rights.

[2] For negative impacts only

Salience

What is salience?

Salience is a foundational concept underpinning how a company should prioritize action to avoid, prevent, and mitigate adverse human rights impacts.

While the concept of “materiality” has its origins in the field of reporting, the term “salience” has its origins in the field of human rights due diligence and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

Salience refers to identifying, prioritizing, and addressing the company’s most important adverse human rights impacts, with salience defined by the scale (how grave), scope (how widespread), irremediable character (how hard to make good) and likelihood of an adverse human rights impact.

What are the differences between impact materiality and salience?

Historically there have been two important differences to note between materiality and salience: (1) materiality is about disclosure, while salience is about management; (2) materiality covers all issues, whereas salience has been limited to human rights impacts.

Are the concepts of materiality and salience converging?

Yes, two significant developments are bringing the concepts of salience and materiality closer together.

First, the 2021 iteration of the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards adopted a revised definition of materiality (see above) that incorporates the scope, scale, irremediable character, and likelihood definitions that underpin the concept of salience and the UNGPs.

Second, the ESRS also propose to adopt a definition of impact materiality based on the concept of salience and the UNGPs (i.e., scope, scale, remediability, likelihood). Further, the ESRS make clear that “the materiality assessment of a negative impact is informed by the due diligence process defined in the international instruments of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.”

In short, the concept of salience is being utilized for disclosure (not just management) and for a comprehensive range of economic, environmental, and social issues (not just human rights). BSR welcomes these developments as enhancing conceptual clarity and generating synergy across previously siloed assessments.

Can a salience assessment be combined with a materiality assessment?

It depends. The harmonization of prioritization criteria between “salience” and “impact materiality” means that a salience assessment can be undertaken as part of a materiality assessment provided the expectations of a salience assessment are met—for example, that impacts on all potentially relevant human rights are considered and that affected stakeholders are engaged. BSR anticipates that this combined approach may become more common over time, especially for companies where salient human rights issues make up a large portion of material matters (e.g., social media companies).

However, we also expect that many companies will choose to keep these two assessments separate, while achieving efficiency, synergy, and harmonization by integrating the results of a salience assessment into a materiality assessment, rather than undertaking duplicative assessments.

Technical Matters

How often should materiality assessments be undertaken?

As a matter of principle, materiality assessments should be reviewed annually as part of the company’s annual reporting cycle when deciding what information to disclose. However, a “full” materiality assessment with extensive stakeholder engagement may not be needed every year and should instead be prioritized to happen alongside major changes, such as mergers and acquisitions, market entry, or significant changes in operating context.

What is the threshold for determining materiality or salience?

Companies should define a cut-off point or threshold above which matters are considered material and / or salient. EFRAG’s guidance on double materiality articulates five levels of impact and states that a topic is material if the assessment shows its impacts as being “critical”, “significant” or “important” and not material if the impacts are deemed “informative” or “minimal”. If a materiality threshold is met for either dimension of materiality (financial materiality or impact materiality), then the company should report on the topic. However, the “where and how” aspects for setting the threshold remains iup to the company’s discretion, noting that (1) setting a threshold likely involves professional judgement rather than quantitative precision, and (2) materiality and salience are not absolute concepts, but relative to the other impacts the company has identified.

Should material or salient issues be further prioritized above a threshold?

In financial reporting a threshold-only approach is typically taken, meaning that all issues crossing a threshold of materiality are disclosed (e.g., risk factors in a Form 10-K), but with little attempt to further prioritize among material issues. By contrast, in sustainability reports many companies have chosen to publish 2x2 matrixes or other similar visuals to convey the relative prioritization of material matters.

BSR believes that either approach is legitimate, but we urge caution when conveying relative prioritization for two reasons: (1) a 2x2 matrix (or similar) can suggest significantly more quantitative precision in relative prioritization than is realistic; (2) a 2x2 matric (or similar) can suggest a collection of independent and mutually exclusive topics, whereas many material matters are interrelated, interdependent, and indivisible.

Should materiality and salience assessments cover a company’s entire value chain, including both upstream and downstream?

Yes. The importance of taking a “whole value chain” approach is emphasized by both the ESRS and the UNGPs.

The ESRS state that “[material] impacts include those connected with the undertaking’s own operations and value chain, including through its products and services, as well as through its business relationships. Business relationships include those in the undertaking’s upstream and downstream value chain and are not limited to direct contractual relationships.”

The UNGPs state that “the responsibility to respect human rights requires that business enterprises: (a) Avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities, and address such impacts when they occur; (b) Seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.”

Is a materiality assessment required for sustainability strategy?

No. Many companies find it useful to undertake a materiality assessment as a step in the creation of strategy to help ensure that strategy focusses resources on the most important matters and set direction; however, materiality assessment is not a requirement for sustainability strategy, which can be undertaken separately from materiality.

Is a salience assessment required for human rights strategy?

Yes. The UNGPs are clear that companies have a responsibility to identify and assess any actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which they may be involved and use this as the starting point for determining appropriate action to prevent and mitigate adverse human rights impacts.

Who should approve the final list of material topics or salient issues?

While third party organizations (such as BSR) may be actively involved in the materiality or salience assessment, as a matter of law and principle the final determination of material topics or salient issues should be made by the company. This determination should be made by the highest governance body in the company.

Sustainability FAQs | Tuesday November 1, 2022

Climate Change and People

This FAQ sets out the BSR perspective on the relationship between climate change and people.

Sustainability FAQs | Tuesday November 1, 2022

Climate Change and People

Preview

This FAQ sets out the BSR perspective on the relationship between climate change and people. Both the physical effects of climate change (e.g., extreme weather events) and the transition to a net-zero economy (e.g., shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy) will have disproportionately adverse impacts on under-resourced and under- served communities and exacerbate the underlying systemic inequities that these communities already face. We believe that climate justice should be central to company action on climate change and address the interlocking elements of access and participation, human rights, just transition, and resilience.

Climate Justice

What is climate justice?

Climate justice is the recognition that climate change (which is primarily caused by humans burning fossil fuels) disproportionately impacts some communities over others and exacerbates underlying systemic inequalities.

Climate justice prioritizes the people and communities that are most likely to be affected by the climate crisis but are least responsible for it, and places the needs, voices, and leadership of those who are the most impacted at the forefront.

What is the connection between justice and climate change?

There are at least three key elements to the connection between justice and climate change, and these set the context for business approaches to climate justice.

- Those least responsible are affected the most: The climate crisis has been caused by those with the economic power and privilege to overconsume resources; however, those least responsible for climate change are also least able to adapt and recover from its impacts.

- Existing inequities exacerbate the impact or risk: Some people are negatively affected due to existing inequities related to income, access to resources, and livelihoods that often correlate with gender, race, disabilities, and other factors. They may also live in regions or countries most affected by the climate crisis (e.g., physical events such as hurricanes and droughts).

- Climate policies have unequal consequences and participation: Policies designed to manage climate change have unequal consequences, and the climate change decision making processes (e.g., emissions reductions, adaptation strategies) often exclude those most affected by the climate crisis.

What is the connection between business and climate justice, just transition, human rights, and resilience?

There are at least four ways in which climate change can disproportionately impact communities facing systemic inequities and where solutions can be focused:

-

Just transition to a net zero economy: The transition to a net-zero economy requires a shift away from fossil fuels—but while necessary, this transition risks leaving behind workers and communities dependent on fossil fuel industries for jobs and livelihoods. For example, women risk being left out of the “green jobs” movement because current operational and technical jobs that are predominantly held by men will be redeployed to similar technical roles in renewable energy development.

-

Human rights in the renewables value chain: The development and procurement of renewable energy can be associated with human rights violations, including land grabs and poor working conditions. For example, renewable energy supply chains require mining of metals and other precious metals for solar cells and batteries, and these industries are associated with conflict and poor working conditions.

-

Resilience to climate change impacts: Extreme weather events, drought, flooding, sea-level rise, heatwaves, and other physical events disproportionately exacerbate systemic inequity, including lack of access to finance, healthcare, and other essentials. For example, low-income Black communities were hit hardest during Hurricane Katrina because they did not have the resources to cope.

-

Access to products and services: Under-resourced communities are more likely to experience energy insecurity and lack access to affordable, efficient, secure, and reliable clean energy. For example, older, cheaper, and more polluting vehicles will be exported to lower income countries while advanced countries shift to an electric vehicle market.

What is “loss and damage”?

“Loss and damage” refers to the consequences of climate change that go beyond what people can adapt to, or when options exist but a community doesn’t have the resources to use them. Loss and damage can result from both extreme weather events and sea level rise, and can be divided into economic losses (e.g., disrupted supply chains) and non-economic losses (e.g., impacts on culture). Loss and damage harms vulnerable communities the most, making it an issue of climate justice. The Paris Agreement recognized the importance of “averting” (mitigation), “minimizing” (adaptation), and “addressing” (loss and damage), with the latter referring to helping people after they have experienced climate-related impacts—such as via funding, financing, and humanitarian assistance after an extreme weather event.

What should companies do to address climate justice?

Companies should ensure justice is central to their climate change strategies. There are few examples of this in practice today, so BSR encourages companies to innovate through one or more of the following three approaches:

-

Define a commitment: Companies should ensure that justice is integrated into climate strategy, policies, practices, and investments, appropriate for their industry, business model, and location.

-

Localize action across the value chain: Companies should co-create solutions and opportunities by first listening to communities most affected.

-

Undertake inclusive advocacy: Companies should promote policy frameworks that address systemic injustices and institutional barriers and amplify the voices of frontline communities in climate policy, such as in relation to “loss and damage”.

Just Transition

What is the just transition?

The International Labor Organization (ILO) defines the just transition as follows: “A Just Transition means greening the economy in a way that is as fair and inclusive as possible to everyone concerned, creating decent work opportunities, and leaving no one behind. A Just Transition involves maximizing the social and economic opportunities of climate action, while minimizing and carefully managing any challenges – including through effective social dialogue among all groups impacted, and respect for fundamental labour principles and rights.”

BSR views the just transition as both an outcome (an inclusive and green future that maximizes the social and economic opportunities for workers and communities) and a process (a partnership with those impacted by the transition to net zero, involving people as active participants in the transition).

What does the Paris Agreement say about the just transition?

Signatories to the Paris Agreement commit to take into account “the imperatives of a just transition of the workforce and the creation of decent work and quality jobs in accordance with nationally defined development priorities.”

What are the ILO Just Transition Guidelines?

Endorsed by the ILO’s Governance Body in 2015, the ILO “Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all” provide non-binding guidance to governments and social partners on the just transition. The Guidelines set out a vision for governments, workers, and employers to use the process of structural change to support a low carbon economy, create decent jobs at scale, and promote social protection.

Are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) relevant to the just transition?

Yes. The relevant SDGs are SDG 8 (“promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all”) and SDG 13 (“take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts”).

What are examples of actions companies can take?

As companies transition out of high-emitting industries and/or energy sources, they need to understand and manage their potential adverse impacts throughout operations, projects, and value chains, including both upstream and downstream. Companies can make the just transition integral to their net-zero plans in the following ways:

-

Identify people (e.g., workforce, communities) who may be impacted by transition plans

-

Engage in social dialogue with workers and their representatives

-

Promote an inclusive workforce transition (e.g., employee training, talent development, or reskilling programs)

-

Engage suppliers of renewable energy to advance just transition principles in company supply chains

The just transition is a systemic challenge beyond the reach of any one company. What else should companies do?

Companies can seek to influence the development just transition policies and strategies of governments in a responsible manner, such as encouraging the adoption of the ILO Just Transition Guidelines, promoting just transition plans in countries, integrating just transition considerations and activities in their own operations and their supply chain, and supporting / funding civil society organizations working to achieve a just transition.

What human rights are at stake in the just transition?

Rightsholders must be central to the just transition as there is potential to impact or cause additional impact to numerous human rights. The most salient human rights include: the right to an adequate standard of living; right to fair renumeration; right to equal pay; right to just and favorable conditions of work; right to rest and leisure; right to peaceful assembly and association; right to form and join trade unions; right to equality and non-discrimination.

Human Rights

Why are human rights relevant to climate change?

The physical impacts of climate change, the transition to a net-zero economy, and the ability of communities to respond to climate change can impact any human rights contained in the International Bill of Human Rights. The impacts of rising global temperatures—natural disasters, the proliferation of vector-borne diseases, climate migration, famine, and drought—will negatively impact many human rights, such as rights to land, shelter, natural resources, mobility, health, employment, and livelihoods.

The transition to a net-zero economy will impact the rights such as an adequate standard of living, equal pay, just and favorable conditions of work, rest and leisure, and the right to form and join trade unions. For example, the development and procurement of decarbonization technology and renewable energy requires the mining of metals and minerals—however, the extraction, production, and disposal of many of these materials are associated with armed conflict, land and water grabs, violation of the rights of Indigenous peoples, the denial of workers’ rights to decent work and a living wage, and other human rights abuses.

Civil and political rights such as privacy, freedom of expression, assembly, and association, and political participation are all essential for the ability of rightsholders and communities to participate in decision-making about how the impacts of climate change are addressed. The absence of adequate protection for human rights— particularly the right to information, participation in decision-making, and access to remedy—magnifies the risk faced by communities who are disproportionately impacted by both climate change itself and our response to it.

The right to share in scientific advancement and its benefits is relevant for access to technologies designed to mitigate or assist with adaptation to climate change.

Finally, the urgent need to address the climate crisis also places new pressure on intellectual property rights and raises new human rights dilemmas, such as how to balance the right to freedom of expression with the desire for a healthy information environment that supports informed decision making (i.e., address climate misinformation).

Is there a right to a healthy environment?

Yes. The right to a healthy environment was acknowledged by the United Nations Human Rights Council in October 2021 and endorsed by the UN General Assembly in July 2022. This right is interconnected with other health-focused human rights, such as the right to water and sanitation, right to food, and right to health.

What responsibility do companies have to address the human rights impacts of climate change?

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) serve as the primary internationally accepted framework for standards and practice regarding human rights and business. According to the UNGPs, companies have a responsibility to respect human rights, which requires that companies (a) avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities and address such impacts when they occur and (b) seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products, or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.

In the context of climate change, this means that companies have:

-

A responsibility to address adverse human rights impacts related to their physical climate impacts

-

A responsibility to address adverse human rights impacts related to their transition to a low-carbon economy

-

An opportunity to promote the realization, fulfillment, and enjoyment of rights in a resilient world.

What is a human rights-based approach to climate change?

Put simply, companies have a responsibility to identify and address the adverse human rights impacts arising from the physical climate impacts of their business operations and the impacts associated with their transition plans. To appropriately fulfill this responsibility, companies should integrate a human rights-based approach into their climate work by consulting with impacted rightsholders, identifying potential adverse human rights impacts arising from their climate strategies, and taking action to address these impacts.

Can companies combine their use of the UNGPs and the TCFD guidelines?

Yes, there is an opportunity to embed an assessment of potential human rights impacts into the climate scenario analysis that companies undertake when implementing the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations or complying with regulatory requirements based on the TCFD.

The TCFD is based on the premise that the most significant effects of climate change will emerge over the medium to longer term, and that their timing, magnitude, and impacts are uncertain. For this reason, the TCFD offers a scenario analysis framework for assessing the potential implications of a range of plausible future states under conditions of uncertainty, allowing companies to understand how various combinations of climate-related risks may evolve over time. We believe there are opportunities to identify the potential human rights impacts of different climate scenarios during this analysis, thereby improving the quality of a company’s human rights due diligence.

We believe there are opportunities to embed climate justice considerations into this analysis to explore how different scenarios may disproportionately impact some communities over others and exacerbate underlying systemic inequalities. This analysis will inform efforts to make climate justice central to company action on climate change.

Access

Why is it important to consider access to energy?

Under-resourced communities are more likely to experience energy insecurity and lack access to affordable, efficient, secure, and reliable clean energy. We need to ensure all communities have equitable access to the resources needed to move to net zero and respond to a changing climate.

For example, small and medium sized enterprises may not have access to the Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) necessary to reach their customers’ net-zero targets, while fuel-combustion vehicles (i.e., older, cheaper, and “dirtier” technologies) may be shipped to lower-income countries while higher-income countries shift to an EV market.

How should companies consider access to energy?

When companies implement net-zero targets across their value chains suppliers will need access to renewable energy to meet their customers’ expectations. However, not all markets have access to clean technologies or renewables in the electrical grid, and under-resourced communities are more likely to experience energy insecurity. Identifying gaps in access to energy across the value chain is an important step to deciding what proactive actions companies can take—such as policy advocacy, financing, and coalition building—to counter inequities in access to clean energy.

Resilience

What is climate resilience?

Climate resilience is the ability to anticipate, prepare for, and respond to the impacts of climate change. Sometimes the terms “adaptation” and “resilience” are used interchangeably, but resilience has become the preferred term. Resilience emphasizes the ability to acquire new capabilities and thrive, whereas adaptation emphasizes using existing resources to navigate changing circumstances.

Why is climate resilience important for people?

It is essential to build resilience to the impacts of climate change—such as extreme heatwaves, floods, droughts, and wildfires—that we cannot prevent and that are endangering health, jobs, and livelihoods. We need to build systemwide resilience to the consequences of climate change that are now unavoidable, while simultaneously strengthening strategies to reduce emissions as quickly as possible in a bid to prevent these impacts from getting any worse.

Individuals and communities are less able to prepare, respond, and recover from extreme weather events and the spread of disease if they lack access to financing, insurance, or healthcare, or if their rights are not protected. Consequently, women, people of color, Indigenous peoples, people with disabilities, children, and the elderly in under-resourced communities are often less able to adapt and build resilience to climate impacts.

What does the Paris Agreement say about resilience?

The Paris Agreement establishes a global goal on adaptation—of enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience, and reducing vulnerability to climate change. The Paris Agreement recognizes that resilience is a global challenge faced by all and emphasizes the importance of technology development and transfer for improving resilience to climate change.

What is the role of business in building climate resilience?

Building resilience to climate change needs to be a driving force behind business strategies, investments, and policies. In doing so, we can ensure that people thrive despite climate change, such as through diverse food systems, regenerative agriculture, and new forms of economic opportunity.

Business can support climate resilience for everyone by helping to ensure that all communities across their value chains are prepared, protected, and able to rebound from climate impacts. Conducting climate risk assessments can be used to identify and understand how climate change is affecting communities across a company’s value chain, and climate resilience can be deliberately integrated into climate scenario analysis frameworks.

Companies can use climate resilience as an opportunity to identify ways to increase access to their products and services (e.g., medicines, technologies, energy, food) and help build resilience equitably. Large companies should be mindful of the need to engage smaller companies (e.g., suppliers, partners, customers) that do not have the capacity to address climate risks and bring them along in the journey—such as by providing access to renewable energy procurement, investing in technology and technology transfer, and other forms of capacity building.

Companies can emphasize the importance of equity and resilience in their public policy activities, such as prioritizing investments for low-income communities.

Sustainability FAQs | Tuesday November 1, 2022

Human Rights Assessment

This FAQ sets out the BSR perspective on human rights assessments. We believe that identifying and prioritizing the actual and potential human rights impacts with which a company may be involved is a first critical step in avoiding, preventing, and mitigating harm to people associated with business activity.

Sustainability FAQs | Tuesday November 1, 2022

Human Rights Assessment

Preview

BSR's perspectives on human rights assessments.

Defining Human Rights Assessment

What is a human rights assessment?

A human rights assessment identifies and prioritizes actual and potential adverse human rights impactsand makes recommendations for appropriate action to address those impacts.A human rights assessment can take many forms, buthas the following key features:

- All Human Rights: A review against all internationally recognizedhuman rights as a reference point since companies maypotentially impactvirtually any of these rights.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups,other relevant stakeholders, and credible independent experts.

- Vulnerable Groups: Identifying whoserights may be adversely impacted, paying special attention to any particular human rights impacts on individuals from groups or populations that may be at heightened risk of vulnerability or marginalization.

- Appropriate Action: Identifying appropriate action to avoid, prevent, mitigate, or remedy actual and potential adverse human rights impacts.

A human rights assessmentidentifies and prioritizesrisks to people (i.e., risks to rightsholders) rather than risks to the business (i.e., risks to enterprise value creation).

When should human rights assessments be undertaken?

Human rights assessments can be undertaken in many different circumstances, such as prior to a new activity or business relationship, prior to major decisions or changes in the operation (e.g., market entry or exit, product launch, or policy change), and / or in response to or anticipation of changes in the operating environment (e.g., rising social tensions).

Human rights assessments can be corporate wide, location based (e.g., country, site), upstream (i.e., supply chain), downstream (i.e., product use), policy oriented (e.g., social media platforms), issue specific (e.g., land rights), or time bound (e.g., reviewing a crisis response). Human rights assessments can also be company specific or sector wide.

How long do human rights assessments take?

In BSR’s experience the length of human rights assessments can vary from less than one week (e.g., prior to an urgent business decision or in reaction to a sudden unexpected events) to two years or more (e.g., prior to a major new product launch or technology innovation). Our standard human rights assessment typically takes 4-6 months.

Is engagement with affected stakeholders a requirement for human rights assessment?

A human rights assessment typically involves meaningful consultation with potentially affected stakeholders, and / or engagement with independent experts, human rights defenders, and civil society organizations. Occasionally engagement with stakeholders is not possible (for example, when an assessment informs an urgent or unanticipated business decision), and here companies should draw upon insights gained from prior stakeholder engagement.

BSR is an independent expert on human rights, and we bring insights from our stakeholder relationships to every engagement; however, effective human rights assessment does require meaningful stakeholder engagement.

Is a human rights assessment the same as human rights due diligence?

No, a human rights assessment is only one part of human rights due diligence. According to the UNGPs, human rights due diligence has four elements:

- Assessment: Assessing actual or potential adverse human rights impacts with which the company may be involved.

- Action: Taking appropriate action to avoid, prevent, mitigate, and / or remedy actual or potential adverse human rights impacts identified in assessments.

- Tracking: Tracking the effectiveness of the company’s response to human right impacts, including via qualitative and / or quantitative indicators and feedback from stakeholders.

- Communications: Communicating externally in a form and frequency such that the company’s approach can be effectively evaluated.

What is a human rights salience assessment?

- Scale: How grave is the impact?

- Scope: How widespread is the impact?

- Remediability: Is it possible to counteract or make good the resulting harm?

- Likelihood: What is the chance of the impact happening?

A salience assessment typically ends with the identification of “salient human rights issues” and does not consider appropriate action to address these impacts.

A human rights salience assessment is one type of human rights assessment. A human rights salience assessment is typically companywide (rather than a specific country, product, or function) and prioritizes actual and potential adverse human rights impacts according to the following criteria:

What is a human rights impact assessment?

A human rights impact assessment is one type of human rights assessment. A human rights impact assessment typically involves more in-depth consultation with affected stakeholders than other forms of human rights assessment, and for this reason is often focused on specific locations or communities.

A human rights impact assessment can provide an in-depth foundation for more nimble, timely, and reactive human rights assessments as circumstances change over time.

Other Assessment Types

What is the difference between human rights and civil rights? What is the difference between a human rights assessment and a civil rights assessment?

Human rights are rights we have simply because we exist as human beings and arenot granted by any state or government. Human rights are inherent to us all, regardless of nationality, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, sexuality, or any other status. By contrast, civil rights arelegal protections granted by governments to their citizens, typically through a national constitution or other laws.

For this reason, a human rights assessment will reviewimpacts against all internationally recognized human rights as a reference point, whereas a civil rights assessment will review impacts against the relevant local legal protections.

While human rights assessments and civil rights assessments aretypically pursued separately (especially in the United States), we believe there are opportunities for significant synergies.

What is the difference between human rights and ethics? What is the difference between a human rights assessment and an ethics assessment?

Human rights assessments are focused one stablished rights that should always be protected and respected, internationally recognized laws and standards, and a universally endorsed framework for defining company responsibility.

By contrast, ethics assessments are useful for decision‑making in situations where right/ wrongand good/bad are not clearly defined, where different pathways of action canreasonablybe chosen, and to address issues of fairness and social justicewhere different schools of thought and ethicalstandards exist.

While human rights assessments and ethics assessments aretypically pursued separately,we believe there are opportunities for significant synergies. A human‑rights‑based approach provides a universal foundation upon which various ethical frameworks, choices and judgments can be applied.

What is the difference between a human rights salience assessment and a materiality assessment?

Historically there have been two important differences between materiality and salience: (1) materiality is about disclosure, while salience is about management; (2) materiality covers all issues, whereas salience has been limited to human rights impacts. However, two significant developments are bringing the concepts of salience and materiality closer together.

First, the 2021 iteration of the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards adopted a revised definition of materiality that incorporates the scope, scale, irremediable character, and likelihood definitions that underpin the concept of salience and the UNGPs.

Second, the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) that specify disclosure requirements under the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive also propose a definition of impact materiality based on the concept of salience and the UNGPs (i.e., scope, scale, remediability, likelihood).

In short, the concept of salience is being utilized for disclosure (not just management) and for a comprehensive range of economic, environmental, and social issues (not just human rights). BSR welcomes these developments as enhancing conceptual clarity and generating synergy across previously siloed assessments.

Can a salience assessment be combined with a materiality assessment?

It depends. The harmonization of prioritization criteria between “salience” and “impact materiality” means that a salience assessment can be undertaken as part of a materiality assessment provided the expectations of a salienceassessment are met—for example, that impacts on all potentially relevant human rights are considered and that affected stakeholders are engaged. BSR anticipates that this combined approach may become more common over time, especially for companies where salient human rights issues make up a large portion of material matters (e.g., social media companies).

However, we also expect that many companies will choose to keep these two assessments separate, while achieving efficiency by integrating the results of a salience assessment into a materiality assessment, rather than undertaking duplicative assessments.

Can human rights be embedded in enterprise risk assessment?

Human rights assessmentcan be included within broader enterprise riskassessment and risk management systems, provided it goes beyond identifying material risks to the company and includes risks to people as well.

The emerging concepts of “double materiality” (the notion that companies should report on matters that influence enterprise value andmatters that affect wider society) and “dynamic materiality”(thenotion that therelative materiality of an issue may change over time) make it likely that the connectivity between enterprise risk assessment and human rights assessment will grow over time.

What is the difference between a human rights assessment and a human rights audit?

A human rights assessment is typically forward looking, identifies and priorities actual and potential human rights impacts, and recommends appropriate actionto address them. By contrast, a human rights audit is typically historical, determines compliance against a standard,investigates the root causes of prior harms, and recommends corrective actions.

Regulatory Requirements

Should human rights assessment berequired by law?

BSR welcomes emerging regulatory requirements that mandate human rights due diligence by companies, which we believe will accelerate urgently needed due diligence, scale best practices, and result in greater attention on human rights impacts by Boards and senior management at companies.We believe these requirements should be as consistent as possible with the UNGPs, enable effective human rights due diligence rather than “check box” approaches, and incentivize ambitious action by companies.

What are the risks associated with human rights assessment being required by law?

There is a risk that companies will seekminimalist complianceandstifle efforts aimedat more ambitious and meaningful human rights due diligence. However, the absence of consistent and structured human rights due diligence at companies today means that regulation is merited, and BSR will promote meaningful human rights due diligence as the inevitabletug of warbetween “the letter” and “the spirit” of complianceunfolds.

Technical Matters

Why is it important to determine whether a company causes, contributes to, or is directly linked to an adverse human rights impact?

Appropriate action to address adverse human rights will vary according to whether the company causes or contributes to an adverse impact, or whether it is involved solely because the impact is directly linked to its operations, products,or services by a business relationship.

Where a company causes an adverse human rights impact, it should take the necessary steps to cease or prevent the impact. Where a company contributes to an adverse human rights impact, it should take the necessary steps to cease or prevent its contribution and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact to the greatest extent possible. Where a company is directly linked to an adverse human rights impact,it should use leverage to prevent or mitigate the adverse impact, and consider ending the business relationship if that is not possible, taking into consideration thepotential adverse human rights impacts of doing so.

Leverage is considered to exist where the enterprise has the ability to effect change in the wrongful practices of an entity that causes a harm.

Further, where a company causes or contributes to adverse impacts it should provide for or cooperate in remediation; where a company is directly linked to an adverse impactit does not havethe responsibility to provide forremediation, though it may take a role in doing so.

Do BSR’s human rights assessments reach conclusions on whether a company causes, contributes to, or is directly linked to an adverse human rights impact?

During most human rights assessments BSR uses the questions below(among others) to assess whether a company causes, contributes to, or is directly linked to an adverse human rights impact. However, in our experience,this analysis is directional rather than specific, since the precise conclusion can vary significantly according to the particulars of a case.

- Will the company’sactions or omissions on their own be sufficient to result in the adverse impact?

- Will the company’s specific products, services, oroperations be involved in thespecificharm?

- Are the company’s due diligence efforts, including efforts to prevent or mitigate the impact, of sufficient quality?

- Will the company take actions (or fail to take actions) that facilitate or enable another entity to cause an adverse impact, where a company’s actions add to the conditions that make it possible for use of a product by a third party to cause a harm?

- Will the companytake actions (or fail to take actions) that incentivize or motivate another entity to cause an adverse impact, where a company’s actions make it more likely that a product or service will be used in ways that cause harm?

Should human rights assessments be published?

According to the UNGPs, companies should publish sufficient information for their human rights approach to be effectively evaluated by stakeholders, and we believe this principle should determine the extent to which the results of human rights assessments are published.

There is often a debate about whether (1) the full human rights assessment should be published, (2) a summary of the assessment should be published, or (3) nothing about the assessment should be published. In our experience the following criteria can help inform a decision:

- Publish in Full: Full disclosure is “decision useful” for external stakeholders and would increase the quality of their work, such as by providing information or analysis they otherwise would not have; full disclosure makes contribution to the broader field; full disclosure would assist the company to avoid, prevent, mitigate, or remedy harm.

- Publish a Summary: Significant parts of the assessment should not be disclosed because of internal and/or external stakeholder safety and security, commercial confidentiality, and / or legal prohibitions.

- Don’t Publish: All of the assessment should not be disclosed because of internal and/or external stakeholder safety and security, commercial confidentiality, and / or legal prohibitions; publication of the assessment itself may have an adverse impact on human rights (e.g., increase tension in conflict affected areas, increased scrutiny by a bad actor or government); human rights risks can be effectively addressed without publication; the assessment is not material to stakeholders and would detract from other disclosures.

People

Helle Bank Jorgensen

People

Alessia D’Ascanio

Alessia works with BSR member companies across industries on sustainability management, including stakeholder engagement, materiality, strategy, and reporting, among other topics. She manages BSR’s Future of Reporting collaboration, a group of companies sharing reporting best practices and tracking the regulatory landscape in the US and EU. Alessia brings with her…

People

Alessia D’Ascanio

Preview

Alessia works with BSR member companies across industries on sustainability management, including stakeholder engagement, materiality, strategy, and reporting, among other topics. She manages BSR’s Future of Reporting collaboration, a group of companies sharing reporting best practices and tracking the regulatory landscape in the US and EU.

Alessia brings with her nearly 8 years of experience in sustainability reporting. Prior to joining BSR, Alessia worked in the financial services sector within sustainability teams managing the publication of sustainability reports and ranking and rating submissions. She also worked at GRI where she helped companies better understand and use the GRI Standards.

Alessia holds a BSc in Agricultural and Environmental Sciences from McGill University in Montreal, Canada. A Canadian and Italian national, she speaks English, Italian and French.

Blog | Monday October 31, 2022

Scenarios Reveal the Urgency of Climate Action for the Food, Beverage, and Agriculture Sector

Explore three future climate scenarios for the food, beverage, and agriculture sector, intended to help companies consider dynamic macro forces in climate plans.

Blog | Monday October 31, 2022

Scenarios Reveal the Urgency of Climate Action for the Food, Beverage, and Agriculture Sector

Preview

Land use, crop production, and the respective food, beverage, and agricultural markets are inextricably linked to climate and will be shaped by rising global temperatures and our response to changing weather patterns.

Events of the last decade have already provided a taster of what we can expect. Chronic weather changes (e.g., altered precipitation patterns) and acute weather events (e.g., severe droughts, floods, and tropical cyclones) will significantly impact agricultural systems. From shifting production zones and reduced yields and nutritional quality of crops, to negative outcomes on farmer livelihoods and well-being, there are serious implications for the food, beverage, and agriculture sector.

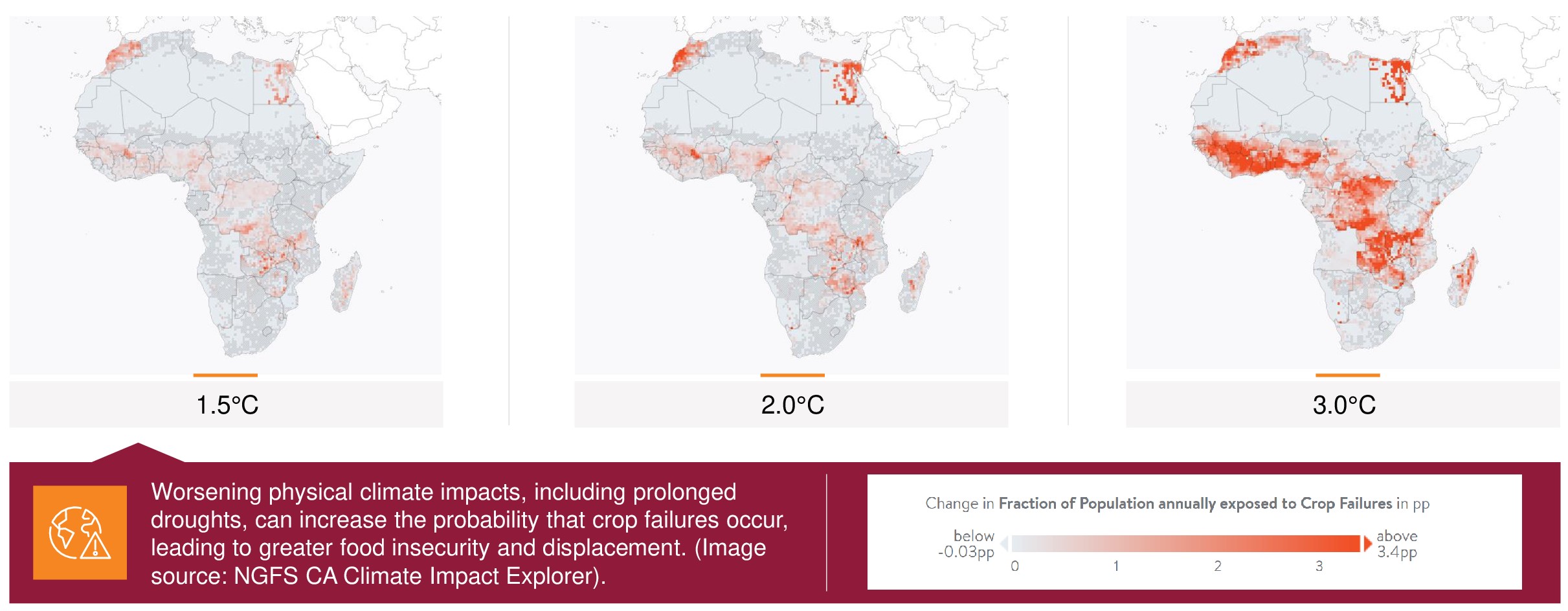

Population Exposed to Crop Failures in Africa

We know that changes to our climate will intensify, bringing environmental, social, and economic turmoil for the global food system. Some of these anticipated impacts will come into effect regardless of future action, as they are linked to greenhouse gases that are already emitted into our atmosphere.

What we don’t know is how society will react in addressing the climate crisis—and thus the severity of its impacts—and how developments in areas such as geopolitics and technology will unfold in the coming decades.

To help companies navigate uncertain futures and consider dynamic macro forces in their climate plans, BSR has developed three future scenarios for the food, beverage and agriculture sector. Below, we share the most salient insights across scenarios, which reinforce the urgency of climate action for business in this sector.

The physical impacts of climate change are relatively certain up to 2035. Beyond this, our action will dictate severity and intensity.

Regardless of action taken to reduce GHG emissions, the physical impacts of climate change are expected to intensify up to 2035. Beyond this, the intensity and frequency of disruptive weather events will be dictated by the speed and ambition of climate action this decade.

Delayed or insufficient action will further increase the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, leading to reduced crop yields and supply chain disruptions that affect access to raw commodities and derived goods.

If we take no further climate action beyond current policies, physical climate impacts in 2050 would lead to global cereal yields that are 15 percent lower than in scenarios where further action is taken. Failing to prepare for such disruptions will likely expose business to greater supply risk and commodity price volatility. The sector will have to build resilience to the expected physical impacts, while working to rapidly achieve net-zero emissions to avoid further catastrophic outcomes.

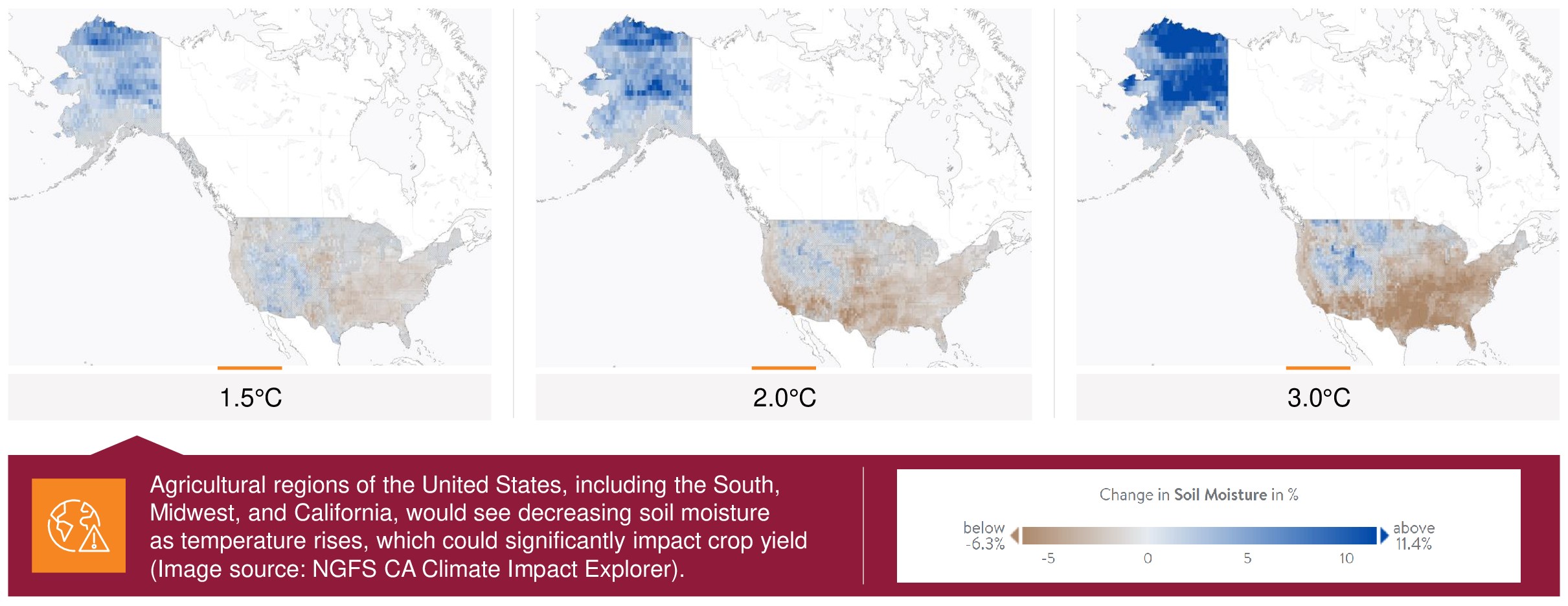

Soil Moisture in the United States

Physical impacts, growth in bioenergy demand, and a greater reliance on land-based carbon sequestration will add pressure on land resources.

On the other hand, rapid and coordinated global climate action may put land resources under greater pressure. Changing weather patterns and demand for both bioenergy and land-based carbon removal will accelerate competition for land resources.

In a scenario where we take early and coordinated action to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century, forested lands would grow by 160 million hectares by 2030, and 15 percent of primary energy would come from biofuels in the same year.

This would require that land—which may already be disputed or under pressure—is used for reforestation, afforestation, and the production of bioenergy crops. If this scenario was to unfold, businesses may be expected to have greater visibility of their supply chains, source materials from regions that are less environmentally vulnerable or free from land disputes and play a central role in driving innovation in agriculture and food and beverage production.

As we target net-zero emissions by 2050, a delay in climate action will leave companies exposed to greater transition risks.

Delayed action would require hasty and draconian approaches to reduce emissions and avert the worst physical impacts. This response could include high carbon taxes and unanticipated legal mandates requiring business to abruptly decarbonize, posing challenges to the food, beverage, and agriculture sector, which tends to have significant value chain and land use emissions.

This precipitated regulatory response would expose companies to high costs for abating emissions, including those linked to rapid deployment of renewable energy, and reliance on low-carbon agriculture technologies that may not deliver the emissions reductions needed or struggle to scale.

Climate scenarios can help food, beverage, and agriculture companies test the resilience of business strategies against plausible futures.

Building climate resilience in the food, beverage, and agriculture sector will require understanding these complex dynamics, preparing for a wide range of plausible futures, and building a strategy that won’t be derailed by any of these futures. Climate scenarios, which highlight sector-specific implications, can be used by business to assess the resilience of sourcing strategies, uncover the vulnerability of key supply chains, and identify climate-related risks and opportunities.

BSR has 30 years of experience working with food, beverage, and agriculture companies on risk assessment and supply chain sustainability. With the launch of this new set of scenarios, we look forward to exploring the implications of plausible future developments related to climate change.

Want to know more about BSR’s FBA Climate Scenarios?

Contact us for a 1:1 briefing on the scenarios, or a 1-hour interactive taster workshop with other industry peers, to see how you can use these scenarios in practice.

Blog | Wednesday October 26, 2022

Social Unrest: Fixing the “S” of ESG in Private Equity

The ESG field is facing increased criticism. Here’s why it’s essential for private equity firms to adopt a human rights-based approach to sustainable investing.

Blog | Wednesday October 26, 2022

Social Unrest: Fixing the “S” of ESG in Private Equity

Preview

The growth of sustainable investing and “ESG” in private equity (PE) signals important progress in the financial industry as investors begin to appreciate how sustainability creates risks and opportunities.

Yet the ESG field is now under fire—for inadequate “greenwashing” strategies or politicized accusations of “bias.” As investors navigate this conflict and seek to maximize the business and societal benefits of sustainable investing, it is imperative that they put impacts on people at the center of their approaches.

The Current State

Common approaches to ESG in PE follow a formula: firms identify material risks to business based on a limited set of pre-determined criteria. If they go ahead with an investment, they encourage portfolio companies to address gaps. There are advantages to this formula, as it fits neatly within a “traditional” understanding of fiduciary duty and is relatively easy to scale.

Yet this formula is not producing adequate results for investors or society. For investors, social issue assessments are often simplistic, “check the box,” murky, and of limited value. These checklists reduce complex issues to simplistic criteria (e.g., having a modern slavery statement or DEI statistics), missing the broader business risks related to the intersection of governance, business models, business relationships and, crucially, real-world impacts of business on people.

Even when an investor looks to address identified risks, the formula often focuses on reducing the financial risk (e.g., by having compliance policies) rather than on the root cause of risk to people (e.g., lack of familiarity with human rights standards, limited engagement with potentially affected people, or regulatory gaps).

For society, the result is often companies that check the right ESG boxes but still have a pernicious effect on workers, communities, customers, and others.

Shifting to a Human Rights-Based Approach

To address these shortcomings, PE firms can strengthen their ESG efforts by adopting a human rights-based approach in alignment with the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

Endorsed by governments in the UN Human Rights Council, the UNGPs offer PE firms a process-based roadmap to respect internationally recognized human rights as a part of core business. This means conducting human rights due diligence to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for how firms and their portfolio companies address risks to people (not just business).

Adopting a human rights approach helps PE firms to:

- Identify social risks and opportunities. Investors should ask tough questions: how do a company’s business model, products and services, and relationships impact people? These questions highlight real-world risks far better than generic questions about policies. For example, an investor recently lamented that using an ESG checklist for software companies was meaningless. The checklist might treat a company that makes accounting software the same as one that surveils employees. By focusing on harms to people, the firm would be better able to distinguish among companies, technologies, and end-use impacts.

- Anticipate legal risks. Investors consider proximate regulatory and legal risks to a business. By assessing the full range of a business’ harm to people, investors can anticipate and avoid the harms that lead civil society and communities to advocate for regulatory and legal action. For example, a 15-minute delivery service may have ESG policies, but its business model relies on precarious working conditions and increases congestion and traffic accidents, leading workers to strike and city officials to consider strict regulations.

- Align with emerging human rights regulations. Governments are adopting policies that reflect the expectations set out by the UNGPs. The proposed European Due Diligence directive will create a de facto Board-level obligation for companies to conduct human rights due diligence to address risks to people. The EU’s movement to “double” or “impact-based” materiality is also grounded in the human rights-based approach. Meanwhile, the US Government is updating its National Action Plan on Responsible Business Conduct to promote uptake of the UNGPs.

- Get ahead of geopolitical risk. Investors should consider human rights risks—especially severe civil and political rights risks—as an early warning system for geopolitical risk. For example, many investors were shocked by the economic withdrawal from Russia following the invasion of Ukraine. Going forward, they should consider, “How should we conduct business in countries where the government systematically violates human rights?”

- Respond to social harms and crises. A human rights approach offers principled and pragmatic guidance that helps companies navigate and respond to broader societal challenges and crises, such as the widespread assault on trans people’s rights across US state legislatures.

Actions for Private Equity

Investors in other asset classes have realized the value of a human rights approach. Investors representing US$7 trillion in assets under management have called on companies to conduct human rights due diligence, while others have called on governments to mandate such due diligence. Human rights are also a focus for the PRI.

To begin integrating human rights into their investment strategies, private equity firms should:

- Build capacity on human rights throughout the firm. Starting with sustainable investing leads and proliferating to portfolio managers and investment teams, firms should understand human rights standards and frameworks.

- Assess current portfolio companies and investment practices. Firms should identify existing or potential adverse human rights impacts before investing and on an ongoing basis once invested and develop plans to address them.

- Develop a go-forward plan for systematic integration of human rights into ESG approaches. Firms should include a human rights lens into investment themes, ESG policies, diligence, portfolio stewardship, etc.

BSR looks forward to building on its decades of work with companies on human rights to help private equity firms use rights-based approaches to build the next generation of sustainable investing.

Blog | Thursday October 20, 2022

Building Competent Boards: ESG Not about “Skills-Washing”

Boards need to understand emerging ESG issues and make informed decisions. Helle Bank Jorgensen, CEO and Founder of Competent Boards, discusses board training and evolution.

Blog | Thursday October 20, 2022

Building Competent Boards: ESG Not about “Skills-Washing”

Preview

In July 2022, I had the pleasure of interviewing Helle Bank Jorgensen, CEO and Founder of Competent Boards at BSR’s Future of Reporting Workshop. Helle and I previously spent a few years as advisory board members to Ethical Corp (now Reuters Sustainability) when she invited me to join her Competent Boards program during a Responsible Business awards ceremony in London in 2019.

Some years later, as part of our BSR Future of Reporting workshop on Boards and Regulation this past July, Helle shared with our 70+ members her experience since the founding of Competent Boards in 2019, with insights on who is seeking board training, what type of training, and what’s next for the evolution of boards.

Here are the key takeaways from our discussion:

- ESG training is not about “skills-washing”—boards now have a duty of care in the new regulatory environment.

- Where previously curious board directors sought training upon recognizing a skills gap, we’re now seeing entire company board cohorts looking to upskill on all issues across ESG.

- “Luck favors those who come prepared.” There is a changed mindset from "why boards should care" to "how do we care about this." This means going beyond compliance to building long-term value creation

- Boards need to have the right insights and foresight for resilience in governance.

- Directors live their values—they must be stewarded and acted upon.

Helle, could you tell us more about Competent Boards?

Competent Boards provides designation and certification programs on ESG and climate for board members and senior business professionals. Boards need to be equipped with knowledge and frameworks that allow them to understand emerging ESG issues and make informed decisions that contribute to the well-being of companies and society. Competent Boards leverages the expertise of over 180 faculty members to equip boards with the knowledge and network needed to succeed.

You launched Competent Boards in 2019 at Davos with astounding success. How have profiles of those who are getting certified evolved over the years?

Before, it was just believers at a personal level who were curious or lifelong learners who joined the program. Now, it is much broader. Professionals today are recognizing their duty and acknowledging the skills gap. ESG training is not about “skills-washing." Directors joining the program want to feel confident that they have the necessary information to anticipate risks and opportunities to the business and how the company can create more value for shareholders and society at large. More and more companies today are therefore asking to work with their entire board instead of just a few individual members. This is a huge mindset shift.

What are boards finding most difficult today in terms of ESG? Is there any one aspect they are struggling with more?

Many board members and professionals today are aware of the climate challenge and need to act in this decisive decade. However, less known and explored–and yet still important in terms of duty of care and duty to act—is human rights. Boards have discovered that this is business too, strategic, often overlooked in terms of major risks, and invisible to hidden risks in supply chains and operations. In Europe, there is now the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive that changes the game and stipulates a board’s duty to act. Many boards today are not ready for this.

How are questions from board members changing?

The biggest change I’m seeing in terms of board mentality is “why boards should care” to “how can we care about this.” I recently said at a World Economic Forum meeting, “luck favors those who come prepared,” and I firmly stand by this. There is a changed mindset from compliance, to accountability, to long-term governance and value creation, versus passive oversight or delegation to other experts in the company. Boards can ensure that they have the right insights and foresight for resilience in governance, including an important baseline knowledge and understanding across E, S, HR, and G.

With today’s shifting regulatory framework and the new role of boards, what’s next?

More scrutiny from stakeholders as well as shareholders. Shareholders are getting sophisticated in their knowledge of ESG and the value drivers for the company. They’re sharp, and they ask far more targeted questions.

I also want to conclude by saying that there is a profound cultural change happening from the inside. Companies must internalize their core values, and this starts at the board level. Boards must live their values—and these values must be stewarded and acted upon. Otherwise, we’re back at where we started—“skills-washing” through ESG.

Helle, thank you for joining us and for a very provocative dialogue. Learn more about Competent Boards certification programs and BSR’s board offering.

Blog | Tuesday October 18, 2022

Building Trauma-Informed Workplaces: Recommendations for Business

Three organizations discuss their programs employing and empowering survivors of human trafficking and their efforts to create a trauma-informed workplace enabling all employees to thrive.

Blog | Tuesday October 18, 2022

Building Trauma-Informed Workplaces: Recommendations for Business

Preview

Modern slavery and human trafficking is on the rise. While the public and private sectors have largely focused on preventing and mitigating these risks, more can be done to address the root causes of labor exploitation.

Safe, sustainable employment is one of the most effective ways to support survivors in securing their livelihood. The private sector is uniquely positioned to provide vocational training, skills and confidence coaching, and entry-level jobs for survivors who seek financial stability.

The Global Business Coalition Against Human Trafficking (GBCAT) recently sat down with three organizations to learn about their programs to employ and empower survivors of human trafficking and their efforts to implement a trauma-informed workplace that enables all employees to thrive. We discussed how they had got started with survivor employment and empowerment, key challenges of adopting a trauma-informed approach, and lessons learned for business.

Here we share some key findings from these conversations to help more businesses implement their own trauma-informed practice.

Three Businesses Employing Survivors of Human Trafficking

While still too few and far between, a variety of organizations are showing leadership in employing survivors of human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. Our case studies highlight three successful examples: